CRAIG JOHN FRANCK

Title: BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

Area:

Country:

Program:

Available for Download: Yes

View More Student Publications Click here

Sharing knowledge is a vital component in the growth and advancement of our society in a sustainable and responsible way. Through Open Access, AIU and other leading institutions through out the world are tearing down the barriers to access and use research literature. Our organization is interested in the dissemination of advances in scientific research fundamental to the proper operation of a modern society, in terms of community awareness, empowerment, health and wellness, sustainable development, economic advancement, and optimal functioning of health, education and other vital services. AIU’s mission and vision is consistent with the vision expressed in the Budapest Open Access Initiative and Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. Do you have something you would like to share, or just a question or comment for the author? If so we would be happy to hear from you, please use the contact form below.

For more information on the AIU's Open Access Initiative, click here.

Executive Summary

In business, risks lurk at every turn, competitor innovations that threaten the viability of your products or services, new players in the market place, adverse trends in commodity prices, currencies, interest rates or the economy. Throw in potential disruptions to supply chains that have been stretched across thousand of miles and country borders by globalization, and the opportunity for something to go wrong is, to say the least, worrisome.

Financial executives, who have not done so already, should begin to develop a holistic risk management program or one that allows them to mitigate and manage risk on a broad front. Organizations who are tempted to short change their risk management efforts will find potential consequences can be severe, from a loss of competitiveness to, in the extreme, having to cease operations altogether.

Risk is often mapped to the probability of some event which is seen as undesirable. Usually the probability of that event and some assessment of its expected harm must be combined into a believable scenario (an outcome) which combines the set of risk, regret and reward probabilities into an expected value for that outcome.

Thus in statistical decision theory, the risk function of an estimator δ(x) for a parameter θ, calculated from some observables x; is defined as the expectation value of the loss function L,

There are many informal methods which are used to assess (or to "measure" although it is not usually possible to directly measure) risk, and (for some applications) formal methods such as value at risk.

In scenario analysis "risk" is distinct from "threat." A threat is a very low probability but serious EVENT WHICH some analysts may be unable to assign a probability in a risk assessment because it has never occurred, and for which no effective preventive measure (a step taken to reduce the probability or impact of a possible future event) is available. The difference is most clearly illustrated by the precautionary principle which seeks to reduce the threat/s by requiring it to be reduced to a set of welldefined risks before an action, project, innovation or experiment is allowed to proceed.

In information security a "risk" is defined as a function of three variables:

If any of these variables approaches zero, the overall risk approaches zero. For example, human beings are completely vulnerable to the threat of mind control by aliens, which would have a fairly serious impact. But as we haven't yet met aliens, we can assume that they don't pose much of a threat, and the overall risk is almost zero. Is the risk negligable, this is often called a residual risk.

Scenario analysis matured during Cold War confrontations between major powers, notably the USA and USSR, but was not widespread in insurance circles until the 1970s when major oil tanker disasters forced a more comprehensive foresight. It entered finance in the 1980s when financial derivatives proliferated. It did not reach most professions in general until the 1990s when personal computers proliferated.

Governments are apparently only now learning to use sophisticated risk methods, most obviously to set standards for environmental regulation, e.g. "pathway analysis" as practiced by the US EPA.

Risk management involves identifying, analyzing, and taking steps to reduce or eliminate the exposures to loss faced by an organization or individual. The practice of risk management utilizes many tools and techniques, including insurance, to manage a wide variety of risks. Every business encounters risks, some of which are predictable and under management's control, and others which are unpredictable and uncontrollable.

Risk management is particularly vital for small businesses, since some common types of losses—such as theft, fire, flood, legal liability, injury, or disability—can destroy in a few minutes what may have taken an entrepreneur years to build. Such losses and liabilities can affect day to day operations, reduce profits, and cause financial hardship severe enough to cripple or bankrupt a small business. But while many large companies employ a full time risk manager to identify risks and take the necessary steps to protect the firm against them, small companies rarely have that luxury. Instead, the responsibility for risk management is likely to fall on the small business owner.

The term risk management is a relatively recent (within the last 20 years) evolution of the term "insurance management." The concept of risk management encompasses a much broader scope of activities and responsibilities than does insurance management. Risk management is now a widely accepted description of a discipline within most large organizations.

Basic risks such as fire, windstorm, employee injuries, and automobile accidents, as well as more sophisticated exposures such as product liability, environmental impairment, and employment practices, are the province of the risk management department in a typical corporation. Although risk management has usually pertained to property and casualty exposures to loss, it has recently been expanded to include financial risk management—such as interest rates, foreign exchange rates, and derivatives—as well as the unique threats to businesses engaged in E commerce. As the role of risk management has increased, some large companies have begun implementing large scale, organization wide programs known as enterprise risk management.

In the 1990s, the field of risk management expanded to include managing financial risks as well as those associated with changing technology and Internet commerce. As of 2000, the role of risk management had begun to expand even further to protect entire companies during periods of change and growth. As businesses grow, they experience rapid changes in nearly every aspect of their operations, including production, marketing, distribution, and human resources.

Such rapid change also exposes the business to increased risk. In response, risk management professionals created the concept of enterprise risk management, which was intended to implement risk awareness and prevention programs on a company wide basis. "Enterprise risk management seeks to identify, assess, and control sometimes through insurance.

The main focus of enterprise risk management is to establish a culture of risk management throughout a company to handle the risks associated with growth and a rapidly changing business environment. Writing in Best's Review, Tim Tongson recommended that business owners take the following steps in implementing an enterprise wide risk management program:

Finally, it is important that the small business owner and top managers show their support for employee efforts at managing risk. To bring together the various disciplines and implement integrated risk management, ensuring the buy in of top level executives is vital. Luis Ramiro Hernandez wrote in Risk Management. "These executives can institute the processes that enable people and resources across the company to participate in identifying and assessing risks, and tracking the actions taken to mitigate or eliminate those risks."

Means of measuring and assessing risk vary widely across different professions The various means of doing so may define different professions, e.g. a doctor manages medical risk, a civil engineer manages risk of structural failure, etc. A professional code of ethics is usually focused on risk assessment and mitigation (by the professional on behalf of client, public, society or life in general).

Some industries manage risk in a highly quantified and numerate way. These include the nuclear power and aircraft industries, where the possible failure of a complex series of engineered systems could result in highly undesirable outcomes. The usual measure of risk for a class of events is then

Risk = Probability (of the Event) times Consequence.

(The total risk is then the sum of the individual class risks)

In the nuclear industry, 'consequence' is often measured in terms of off site radiological release, and this is often banded into five or six decade wide bands.

The risks are evaluated using Fault Tree/Event Tree techniques. Where these risks are low they are normally considered to be 'Broadly Acceptable'. A higher level of risk (typically up to 10 to 100 times BA) has to be justified against the costs of reducing it further and the possible benefits that make it tolerable these risks are described as 'Tolerable’. Risks beyond this level are of course 'Intolerable'.

The level of risk deemed 'Broadly Acceptable' has been considered by Regulatory bodies in various countries an early attempt by UK government regulator & academic F. R. Farmer used the example of hill walking and similar activities which have definable risks that people appear to find acceptable. This resulted in the so called Farmer Curve, of acceptable probability of an event versus its consequence.

The technique as a whole is usually refered to as Probabilistic Risk Assessment (PRA), (or Probabilistic Safety Assessment, PSA).

Risk in finance has no one definition, but some theorists, notably Ron Dembo, have defined quite general methods to assess risk as an expected after the fact level of regret. Such methods have been uniquely successful in limiting interest rate risk in financial markets. Financial markets are considered to be a proving ground for general methods of risk assessment.

However, these methods are also hard to understand. The mathematical difficulties interfere with other social goods such as disclosure, valuation and transparency. In particular, it is often difficult to tell if such financial instruments are "hedging" (decreasing measurable risk by giving up certain windfall gains) or "gambling" (increasing measurable risk and exposing the investor to catastrophic loss in pursuit of very high windfalls that increase expected value).

As regret measures rarely reflect actual human risk aversion, it is difficult to determine if the outcomes of such transactions will be satisfactory. Risk seeking describes an individual who has a positive second derivative of his/her utility function. Such an individual would willingly (actually pay a premium to) assume all risk in the economy and is hence not likely to exist. In financial markets one may need to measure credit risk, information timing and source risk, probability model risk, and legal risk if there are regulatory or civil actions taken as a result of some "investor's regret".

Figure. 1. Business Risk Analysis Tool

The concepts of closeness to the core business and market attractiveness can be combined to analyze the risk of investing in new offerings. The proximity of the new offering to the core business is measured by its proximity to current offerings and current markets.

The expert system will position your enterprise on the chart based upon your description of:

You can trace through the supporting analysis and its conclusions, adjusting your input until you are satisfied your description accurately characterizes your enterprise.

Analysis of Your Enterprise Position |

|||

Ideal |

Risky |

Low Potential |

Poor Prospect |

Close to Core Business |

Distant from Core Business |

Close to Core Business |

Distant from Core Business |

Offerings in this category represent the least risk and will be ideal candidates for development. |

Offerings in this quadrant are risky to develop since they stray from the core business. They will need a high level of investment, both in terms of resources and expertise. Proceed only if the long term corporate strategy is intended to develop in this way. |

The decision to proceed should be based on the evaluation of the market potential. The low attractiveness of the market may be a benefit since it will be less lucrative for competitors. |

Offerings in this quadrant are poor prospects. They depart from the core business and offer low market attractiveness |

Figure. 2. Results based on the Outcome of Risk Analysis Tool

Can the original product or service idea actually be created?

If the product can be developed, can it actually be produced in appropriate volume?

If the product can be made, can it be sold effectively?

If the product can be sold effectively, will the resulting company be profitable and can the profits actually be realized in a form that allows investors to receive cash

If the company can achieve operating profitability at one level, can profitability be maintained as the company grows and evolves?

The universe of uncertainty that each company faces is comprised of endogenous and exogenous dimensions. Endogenous uncertainty arises from the nature of the internal (i.e. project and organization level) environment. Exogenous sources of uncertainty, in turn, arise at three levels: industry, competition and external environment.

Industry level uncertainties originate primarily from technological innovation and changes in the relative prices of inputs and outputs. Competitive risk represents the degree to which competitors' actions cannot be predicted, and may therefore bring about unanticipated consequences. Uncertainty in the external environment refers to the risk present in the operating environment of a given country.

Environmental uncertainty arises from the prospect of political, macro economic, social, natural, financial and currency volatility, and is often represented by the term country risk (Clark and Marois, 1996, Howell, 1998 and Robock, 1971).

Academic usage of the terms risk and uncertainty has been shaped by Knight's (1921) assertion that the former entails uncertain outcomes of known

probabilities, while the latter entails uncertain outcomes of unknown probabilities. Volatility, in turn, is typically equated with the statistical measure of variance (or standard deviation), and as such is an ex post measurement of risk and/or uncertainty.

Among practitioners, however, the most important aspect of all three terms is the unpredictable nature of potentially detrimental outcomes, or in more colloquial terms “the future is no longer what it used to be” (Hausmann et al., 1995). For instance, in a survey of financial analysts, Baird and Thomas (1990) found the most common definitions of risk used by the analysts were;

In the same survey, the item that was least associated with risk was the Knightian definition of risk as known probabilities and outcomes. Unlike gambling, business strategy entails outcomes of unknown or uncertain probabilities, and the nature of the outcomes themselves may be unknowable. Also, drawing from real options thinking (e.g. Amram and Kulatilaka, 1999, McGrath and MacMillan, 2000 and Trigeorgis, 1996),

The analysis of country risk is a well established field within international business research which demonstrates a clear relevance to practice. Country risk analysis is intended to isolate idiosyncratic sources of potential volatility in a country's political, economic, or social environment. In line with the manner in which most practitioners conceptualize risk, the principal objective behind country risk analysis has been the minimization of downside risk.

The formal evaluation of country risk grew out of the need to evaluate the creditworthiness of sovereign nations, and was extended within the financial sector to evaluate private foreign entities. Most large international banks maintain departments specifically responsible for monitoring country risk, and many of these offer clients formal, standardized analyses of country risk.

In addition, consultancies and business information providers such as the Economist Intelligence Unit, Credit Risk International, International Business Communications, Institutional Investor, and Euromoney routinely conductstructured analyses of country risk, which are disseminated to clients in the form of standardized reports and customized services.

Clark and Marois (1996) summarize the methodologies employed by some of these organizations, which typically utilize a weighted average of objective economic and political data (e.g. change in GDP, GDP per capita, industrial costs, number of political uprisings) as well as a survey of experts to arrive at an aggregate measurement of country risk.

Cosset and Roy (1991) found the primary determinants of the ratings generated by Euromoney and Institutional Investor are per capita income and the country's propensity to invest and level of indebtedness.

Due to the lack of competing methodologies, the country risk analysis techniques that were developed for use in the financial sector are now applied with few or no changes for the purpose of evaluating country level uncertainties in the operating environment (Clark & Marois, 1996). Country risk scores are typically used to discount the value of potential investments in a given foreign country, such that potential projects in higher risk countries are subjected to a higher discount rate (or must exceed a higher hurdle rate of return).

The commonly employed practice of accounting for the downside risk associated with potential private foreign direct investment based on country risk measures that were originally designed to evaluate sovereign risk is likely inappropriate, for four main reasons. First, the risk of default in international lending is not necessarily equivalent to other risks faced in international business. A measurement of financial risks is unlikely to accurately represent economic, social, currency and political risks.

Second, lending situations are fundamentally different from other forms of international business, in that only downside risk is relevant in a lending context (i.e. if a borrower is more successful than anticipated, they do not pay a higher interest rate).

Third, the generation of a generic country risk rating does not account for firm specific factors, such as exposure, aversion to risk, and ability to manage risk.

Fourth, the current ways in which country risk is measured do not effectively gauge the most commonly perceived definitions of risk. For instance, an average of analysts' expectations of GDP growth is frequently incorporated into country risk measures (Clark & Marois, 1996), with lower growth reflecting higher risk.

However, this measure confounds expected return with risk, and does not directly assess the predictability of GDP growth.

At best, country risk rating methods help increase managers abilities to anticipate or identify changes in the operating environment. But these methods do not measure the predictability of the environment or the chance and size of a detrimental outcome. Therefore, country risk measures are unlikely to truly capture the nature of risk as conceived by practitioners.

The conceptual concerns with country risk measures outlined in Section 1.2 are corroborated by empirical research evaluating the extent to which country risk measures are effective predictors of macro level volatility. In a recent study, Oetzel et al. (2001) examined the performance of 11 widely used measures of country risk during a 19 year period across 17 countries. The authors found that none of the sampled measures was effective in predicting periods of significant volatility.

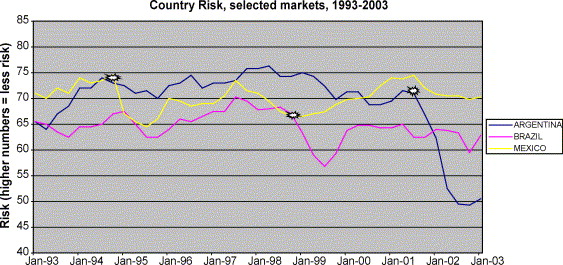

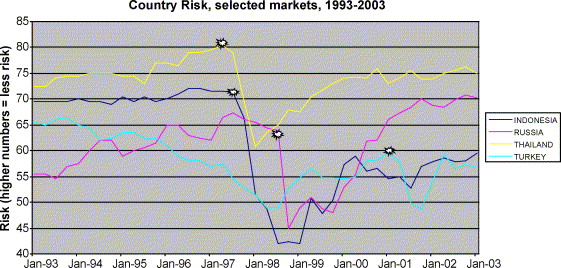

A further demonstration of the shortcomings inherent in relying upon established measures of country risk is depicted in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. Each figure depicts a decade (1993–2003) of quarterly country risk measures from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) (www.countrydata.com).

The ICRG risk measures are widely used by both practitioners and academics (e.g. La Porta, Lopez de Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1997) to capture the various dimensions of country risk and identify potential volatility. The measures shown represent a composite measure of country risk, which consists of an aggregate of political risk, economic risk and financial risk.

The figures include seven major emerging markets, which were chosen on the basis of each having experienced at least one major economic crisis during the sample period, and collectively these countries account for the most prominent emerging market economic crises in the past decade. In each case, the quarter in which the crisis first materialized is indicated with a special symbol.

Figure. 3. Illustrative evidence of the ineffectiveness of country risk measures in predicting volatility ex ante.

Figure. 4. Illustrative evidence of the ineffectiveness of country risk measures in predicting volatility ex ante.

As shown in the illustrative cases depicted in these figures, a well established measure of country risk failed to clearly predict any of the crises. In fact, in a majority of cases, the focal country was deemed to be exhibiting diminishing risk in the periods leading up to a major crisis.

For instance, Mexico's country risk rating increased (i.e. improved) consistently in 1993 and 1994, only to collapse after the December 1994 peso devaluation. In an even more extreme case, Thailand's country risk rating climbed from 73 to above 80 in the 2 year period preceding the crisis which

started in July 1997 and eventually spread to most of Asia and other emerging markets. After the crisis materialized, Thailand's country risk rating fell to 60

Not all risks are created equal. Some risks, such as those related to supply chain or property, only have downside consequences. There’s never a benefit to running out of a key component because your supplier can’t get his or her hands on critical raw material, or losing a manufacturing facility to a fire or flood. Other risks, the economy, competition, currency trends and client demand are best described as variable, because they may have positive or negative consequences.

The economy can reduce demand for your product or service during a recession, but it can also stimulate demand during an expansion. Similarly, a new technology could either threaten the viability of your business model, or give you an advantage over the competition, depending if you where the first or last to embrace the technology.

Downside risks, while seen as the most likely to impact the top revenue driver, tend to be easiest to manage, because companies can take proactive measures to minimize or mitigate them, such as building redundancies into their supply chain or installing fire protection systems in offices and manufacturing plants.

In contrast, companies have little control over variable risks. That doesn’t mean companies shouldn’t attempt to manage variable risks. Successful organizations often get that way by using their skills in forecasting, planning, marketing and research and development to leverage variable risks to their own advantage. Companies should focus on eliminating as many downside risks as possible so they can maximize the time spent managing and exploiting variable risks, adds real value to the business.

Whatever the potential benefits of a strong risk management program, many organizations see plenty of challenges to implementing one. The biggest risk management challenge is as expected, will be obtaining adequate resources, namely, time, budget and people. New risks will be introduced through the development of new products, the introduction of new technology, and changes attributable to merger and acquisition activity. When leadership does not embrace a culture of risk management, risk improvement initiatives can be doomed from the outset.

Companies need to make sure they develop risk management programs that work. Besides addressing both variable and downside risks on an enterprise wide basis, programs are needed that should incorporate systems and processes for preventing, not just insuring against common risk factors. Insuring against the downside impact of risk factors should be a company’s last and not first line of defence.

According to C. Arthur Williams Jr. and Richard M. Heins in their book Risk Management and Insurance, the risk management process typically includes six steps. These steps are

The primary objective of an organization, growth, for exampl will determine its strategy for managing various risks. Identification and measurement of risks are relatively straightforward concepts. An Earthquake may be identified as a potential exposure to loss, for example, but if the exposed facility is in New York the probability of an earthquake is slight and it will have a low priority as a risk to be managed.

Businesses have several alternatives for the management of risk, including avoiding, assuming, reducing, or transferring the risks. Avoiding risks, or loss prevention, involves taking steps to prevent a loss from occurring, via such methods as employee safety training. As another example, a pharmaceutical company may decide not to market a drug because of the potential liability.

Assuming risks simply means accepting the possibility that a loss may occur and being prepared to pay the consequences. Reducing risks, or loss reduction, involves taking steps to reduce the probability or the severity of a loss, for example by installing fire sprinklers.

Transferring risk refers to the practice of placing responsibility for a loss on another party via a contract. The most common example of risk transference is insurance, which allows a company to pay a small monthly premium in exchange for protection against automobile accidents, theft or destruction of property, employee disability, or a variety of other risks. Because of its costs, the insurance option is usually chosen when the other options for managing risk do not provide sufficient protection. Awareness of, and familiarity with, various types of insurance policies is a necessary part of the risk management process. A final risk management tool is self retention of risks—sometimes referred to as "self insurance." Companies that choose this option set up a special account or fund to be used in the event of a loss.

Any combination of these risk management tools may be applied in the fifth step of the process, implementation. The final step, monitoring, involves a regular review of the company's risk management tools to determine if they have obtained the desired result or if they require modification. Nation's Business outlined some easy risk management tools for small businesses: maintain a high quality of work, train employees well and maintain equipment properly, install strong locks, smoke detectors, and fire extinguishers, keep the office clean and free of hazards, back up computer data often, and store records securely offsite.

As with so many business initiatives, the success of a risk management programme depends on the active support of senior management.

Effective risk management programs do not rely on the work and resources of any single person or group within the organization. While often led by a risk management officer, the best programs draw on the input and co operation of every part of the organization.

Risk management programs work best and companies reap the greatest possible benefit from them when their goals, processes and results are shared with all the company’s stakeholders.

The best risk management programs not only address all the risks to which modern corporations are susceptible, they also consider how these various

risks can affect the company’s stakeholders and operations.

Effective risk management programs do not merely insure companies against downside risks, they also include proactive systems and processes to maximize the opportunities the opportunities presented by variable risks.

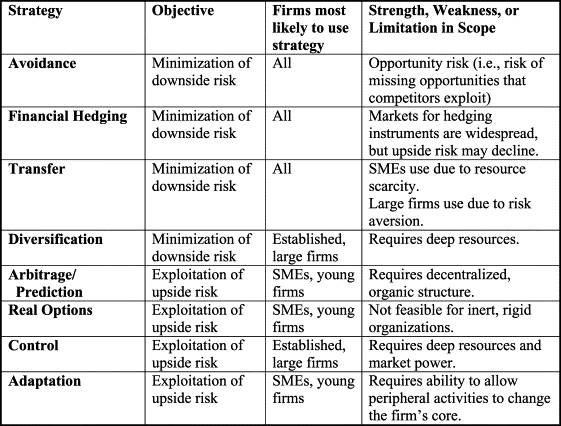

the selection of an appropriate strategy is likely to depend on characteristics of the firm, its industry and competitive environment, the resources and markets accessible in different countries, the modes of entry that are feasible to enter those countries, and other factors.

While many of these factors are idiosyncratic in nature, the relation between strategies for managing country risk and the size and/or age of the firm is likely to be more systematic, given that there are predictable differences in the ability, motivation, and awareness of large, established firms versus SMEs and young firms. Large, established firms are likely to have greater resources and more market power, which will likely lead them to pursue strategies such as diversification and control to manage country risk.

SMEs and newly established ventures, on the other hand, typically exhibit resource scarcity but also maintain organic, decentralized, and flexible organizational structures, which may give them an advantage in the implementation of strategies that require a willingness to change, particularly when change is driven by information acquired in international operations, which are generally peripheral to the organization's core.

This means that SMEs and young firms may be more likely to pursue arbitrage/prediction, real options, and adaptation strategies, though large, established firms are not necessarily precluded from pursuing these strategies as well. An overview of the eight strategies, their objectives, and their scope is presented in Figure. 5.

Figure. 5. Conventional and entrepreneurial strategies for managing country risk.

Small businesses encounter a number of risks when they use the Internet to establish and maintain relationships with their customers or suppliers. Increased reliance on the Internet demands that small business owners decide how much risk to accept and implement security systems to manage the risk associated with online business activities. "The advent of the Internet has provided for a totally changed communications landscape.

Conducting business online exposes a company to a wide range of potential risks, including liability due to infringement on copyrights, patents, or trademarks, charges of defamation due to statements made on a Web site or via e mail, charges of invasion of privacy due to unauthorized use of personal information or excessive monitoring of employee communications, liability for harassment due to employee behavior online, and legal issues due to accidental noncompliance with foreign laws.

The importance of risk management in projects can hardly be overstated. Awareness of risk has increased as we currently live in a less stable economic and political environment.

Making a sound business case for having a strong risk management program has long been an elusive challenge for many organizations. The question still remains unanswered, “How much value should be placed on preventing loss from a disaster that might never happen?” However it is generally agreed that the consequences of risk management failure can be dire. There is a clear imperative for many companies to develop a strong, consistent, enterprise wide risk management programme, as most prevalent business risks will either remain at current levels or increase.

In pursuing this goal, companies, now more than ever, would do well to begin by identifying their top drivers, then pinpointing the top threats to those revenue drivers, and distinguishing between those that are predominantly downside risks and those that are predominantly variable risks.

While both categories of risk deserve attention, companies may discover the effectiveness of their risk management programs are most effective if they devote more of their attention to controlling risk rather than transferring it to insurance companies. And the risks that can be most directly controlled are downside risks, the very risks that are most likely to threaten company’s top revenue drivers. When downside risks are dealt with first through prevention and control, it enables senior management to deal more aggressively with variable risks. In short they become more proactive and strategic with their risk management approach.

Because companies indicate that they expect having trouble finding the time, budget and people necessary to implement or maintain a strong risk management program, senior management must demonstrate leadership in championing and funding this initiative. The number one consequence of poor risk management is loss of competitiveness.

By implementing an effective risk management program, companies protect their ability to compete. Nothing is more fundamental to business success.

Amram, M., & Kulatilaka, N. (1999): Real options. Harvard Business School Press.

Chapman, C., & Ward, S. (1997): Project risk management. JOHN WILEY & Sons.

Courtney, H., Kirkland, J., and Viguerie, P. (1997): Strategy under uncertainty. Harvard Business Review. November/ December

Kagan, C. B. and Ford, D.N. (2002): Using Options to Manage Dynamic Uncertainty in Acquisition Projects. Acquisition Review Quarterly Fall 2002

Barnett, M.L. (2005): Paying attention to real options. R&D Management Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Hausmann, R., Sturzenegger, F. (2007): The Valuation of Hidden Assets in Foreign Transactions: Why “Dark Matter” Matters. The Journal of the National Association for Business Economics, Volume 42, Number 1

Knight, F. H. (1921): Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Peter Romilly, P. (2007): Business and climate change risk: a regional

time series analysis. Journal of International Business Studies.

Ephraim Clark, E., Marois, B. (1996): Managing Risk in International Business. Intl Thomson Business Press.

Oetzel, J.M., Bettis, R.A. and Zenner, M. (2001): Country Risk Measures:

How Risky Are They? Journal of World Business