DOCTOR OF SCIENCE

In the subject

ANTHROPOLOGY

At the

ATLANTIC INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY

NORTH MIAMI, FLORIDA

PROMOTER: DR. P NTATA

Head of Sociology, University of Malawi

January 2005

Chapter 1: Introduction

Socio-Economic Situation in Malawi

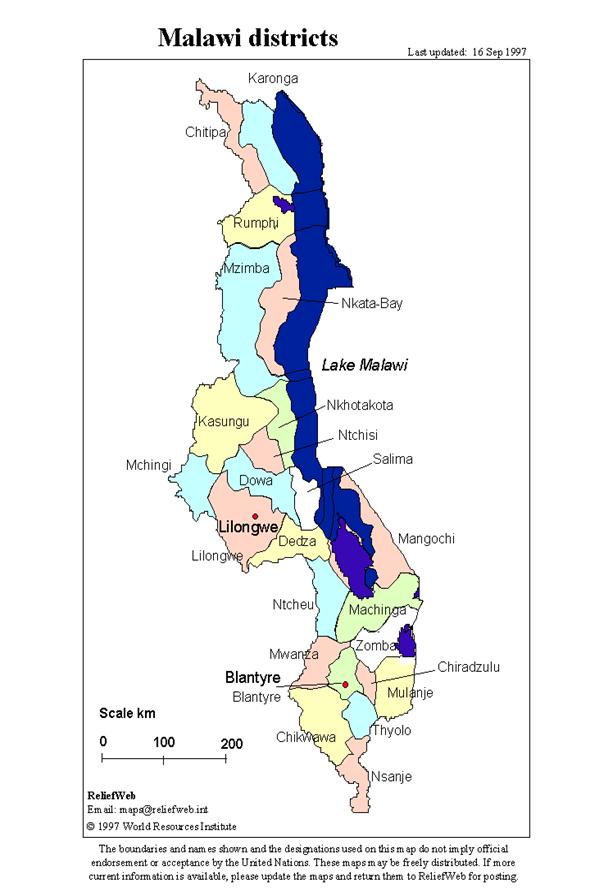

Malawi has a total area of 11.85 million hectares out of which 2.43 million are covered by Lake Malawi. Malawi has a population of 9,933,868 according to the 1998 population census, with an average annual growth rate of 2 percent (1987 – 1998). The rural population constitutes 86 percent of the total population whilst 14 percent of the population resides in the urban areas. Based on the 1998 Population Census, Malawi’s population density is 105 persons per square kilometer with Blantyre and Chiradzulu Districts having the highest population densities, 402 and 308 persons per square kilometer respectively.

Malawi is divided into three regions namely Northern, Central and Southern regions. Within each region, the country is further subdivided into administrative districts. As of now, there are a total of 27 administrative districts in the country. One of the districts is an island on Lake Malawi in the northern region and has a population of 8,074 persons. The northern region has 6 administrative districts; the central region has 9 whilst the southern region has 12. Each district is subdivided into Traditional Authorities (TAs) and each Traditional Authority is further subdivided into Villages.

Malawi’s economy is agro-based. Agriculture accounts for more than 35% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and it employs 50% of the labour force while contributing about 90% of the domestic export earnings.

Just like many other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Malawi faces problems in the agriculture and natural resources sector. These include rural poverty, increasing population with limited agricultural land, loss of forests, decreasing fish and biodiversity; erratic and unreliable rainfall patterns; high incidences of pests and diseases; lack of labour saving technologies, low mechanization levels; declining soil fertility; inferior crop varieties; insufficient post harvest technologies; poor processing and utilization of value adding processes and declining livestock populations. HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Tuberculosis and drug abuse especially among the youth and children are also common problems. These problems have worsened the country’s socioeconomic status where more than 64% of the population is now estimated to live below the poverty line .

Statement of the Problem

Malaria (from Italian referring to "bad air"; and also formerly called ague or marsh fever in English) is an infectious disease which has been with us since time immemorial. Malaria in humans is caused by four species of protozoa parasites of the genus plasmodium: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae. Of the four species, P. falciparum accounts for most of the infections in Africa and for over one third of the infections in the rest of the world. The clinical symptoms of Malaria are caused by the development of the parasites in the red blood cells. Falciparum malaria is the most dangerous form of the disease, resulting in life threatening complication such as anaemia and cerebral malaria. Although Malaria causes intense fever in its victims, cerebral malaria is the most dreaded form, often resulting in death within 24 hours. Malaria usually produces symptoms similar to "flu" only much more severe. These include a high temperature, recurring bouts of feeling cold and shivery, profuse sweating, hot flushes, general aching, and dizziness and delirium. Malaria can lie dormant for months and reoccur even after initial treatment.

Partial immunity develops over time through repeated infections, and without recurrent infection, immunity is relatively short-lived. Therefore, the pattern of exposure to malaria infection, the type of treatment, and the degree of compliance with an ant malarial regimen, local drug resistance patterns, and an individual’s age and genetic make up all tend to influence the severity of the disease.

Rapid identification and treatment of malaria can avert most deaths. Nonetheless it is estimated that malaria is probably responsible for between 500,000 and 1.2 million deaths annually, mainly in children under the age of five years. Studies in Gambia have shown that 52% of malaria deaths occur within the first 48 hours of on set of signs and symptoms, emphasizing the need for prompt and appropriate action as soon as symptoms appear (Greenwood 1987 cited in Hudelson 1995:3). The signs and symptoms of malaria, however, are often not specific and may be confused with other diseases such as pneumonia, respiratory tract infections, gastroenteritis and tuberculosis .

In order to improve identification and management of malaria in children, there is need to know what signs and symptoms families recognize when their children have malaria, how they interpret and respond to these signs and symptoms, and what kinds of care and advice they receive from health care providers. This study tries to describe the factors that influence the management of malaria in children.

How Malaria Spreads

Malaria is passed on to humans by the bite of an infected female mosquito of the genus Anopheles. When the mosquito bites a person, it passes on a parasite called Plasmodium -- which lives and breeds in the mosquito’s stomach -- into the human bloodstream where it is carried to the liver and eventually multiplies. It is also passed from mother to child during pregnancy. Malaria often acts together with malnutrition, respiratory infections and other diseases that prey upon the most vulnerable.

Figure 1: Mosquito of the species anopheles

Extent of the Problem

Globally malaria accounts for about 350-500 million infections and approximately 1.3 million deaths annually, mainly in the tropics . Over 90% of malaria cases and deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of those who die are children aged under-five years. They die because they are unprotected from mosquito bites and are not treated quickly enough with anti-malarial drugs to prevent the disease from killing them.

In malaria-endemic countries pregnant women are at a much higher risk of becoming sick from the disease. Malaria infections during pregnancy may cause maternal anaemia and lead to an increased risk of maternal death. Malaria in pregnancy also increases the risk of miscarriage and still birth. Babies born to mothers with malaria often have low birth weight, which adversely affects the health and development of the child.

In general more than two billion people, nearly 40 percent of the world’s population is at risk for malaria.

Solution

Widespread prevention and prompt treatment are the focus of efforts to fight malaria. A third of malaria deaths could be prevented if children at risk slept under insecticide-treated nets. Currently, however, less than 5% of children at greatest risk of the disease sleep safely under these nets. With social marketing strategies, nets can be promoted and made available to communities at risk.

Chloroquine and Fansidar (SP) have long been used to treat malaria, but in recent years have lost effectiveness. Artemesinin-based combinational therapy (ACT) acts quickly on malaria parasites in the blood stream and has not, up to now, led to the development of resistance. Pregnant women, who are particularly vulnerable to infection, should receive intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) in order to reduce the risk of transmission of malaria. IPT also reduces anemia in pregnancy as well as the resultant low birth weight. SP is the drug that is currently being used because it entails a single dose treatment and is safe. It is, therefore, vital to implement ACT in order to avoid growing resistance to SP so that it is not lost as a frontline drug for IPT. ACT is not yet widely implemented as a first-line response to malaria because it is up to ten times more expensive than the other two drugs, and donors are loath to foot the bill.

In areas of high seasonal malaria transmission, other mosquito-control measures continue to play an important role. Monitoring of mosquito populations is also critical for assessing whether resistance to the currently-used insecticides is emerging and whether there is a need to switch to other insecticides which are more effective in residual spraying.

The Cost of Tools to Roll Back Malaria is not very expensive by international standards. The cost of an insecticide-treated net is about $4.00 and even less in some cases and ACT drugs are available at a cost of about $1.10 per dose. In Africa most of the people live on less than US$1 per day . This can make the cost of rolling back malaria insurmountable.

Chigowo, MT, Chilimba, AD, Luhanga,J. 2000. Alternative Crops in Drug Producing Areas and Capacity building for drug testing in Malawi. Chitedze Agricultural Research Station: Lilongwe.

Nwanyanwu, OC., Kumwenda, N.,Jemu, S., Ziba, C., Kazembe, PN.,and Redd, SC. 1994. Malaria and HIV infection among sugar estate workers in Malawi. CDC, Atlanta.

African Union Commission. 2005. An African Common Position on the Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Figure 1: Mosquito of the species anopheles

Extent of the Problem

Globally malaria accounts for about 350-500 million infections and approximately 1.3 million deaths annually, mainly in the tropics . Over 90% of malaria cases and deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of those who die are children aged under-five years. They die because they are unprotected from mosquito bites and are not treated quickly enough with anti-malarial drugs to prevent the disease from killing them.

In malaria-endemic countries pregnant women are at a much higher risk of becoming sick from the disease. Malaria infections during pregnancy may cause maternal anaemia and lead to an increased risk of maternal death. Malaria in pregnancy also increases the risk of miscarriage and still birth. Babies born to mothers with malaria often have low birth weight, which adversely affects the health and development of the child.

In general more than two billion people, nearly 40 percent of the world’s population is at risk for malaria.

Solution

Widespread prevention and prompt treatment are the focus of efforts to fight malaria. A third of malaria deaths could be prevented if children at risk slept under insecticide-treated nets. Currently, however, less than 5% of children at greatest risk of the disease sleep safely under these nets. With social marketing strategies, nets can be promoted and made available to communities at risk.

Chloroquine and Fansidar (SP) have long been used to treat malaria, but in recent years have lost effectiveness. Artemesinin-based combinational therapy (ACT) acts quickly on malaria parasites in the blood stream and has not, up to now, led to the development of resistance. Pregnant women, who are particularly vulnerable to infection, should receive intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) in order to reduce the risk of transmission of malaria. IPT also reduces anemia in pregnancy as well as the resultant low birth weight. SP is the drug that is currently being used because it entails a single dose treatment and is safe. It is, therefore, vital to implement ACT in order to avoid growing resistance to SP so that it is not lost as a frontline drug for IPT. ACT is not yet widely implemented as a first-line response to malaria because it is up to ten times more expensive than the other two drugs, and donors are loath to foot the bill.

In areas of high seasonal malaria transmission, other mosquito-control measures continue to play an important role. Monitoring of mosquito populations is also critical for assessing whether resistance to the currently-used insecticides is emerging and whether there is a need to switch to other insecticides which are more effective in residual spraying.

The Cost of Tools to Roll Back Malaria is not very expensive by international standards. The cost of an insecticide-treated net is about $4.00 and even less in some cases and ACT drugs are available at a cost of about $1.10 per dose. In Africa most of the people live on less than US$1 per day . This can make the cost of rolling back malaria insurmountable.

Malaria Case Management in Malawi

Malaria is a serious health problem in Malawi especially for the children. In Malawi malaria is responsible for 39% of all out patient visits and 29% of all hospital admissions. Of all deaths occurring to children under five years of age, 10 % were due to malaria. No part of Malawi is free from malaria but most areas experience seasonal variations in epidemiology associated with the breeding habits of the mosquito (Mtoto, 1995).

Malaria is hyper endemic in Zomba district just like many other parts on Malawi. Zomba is located in the southern part of Malawi (see Map of Malawi). The temperatures in Zomba are very suitable for the multiplication of mosquitoes. In 1992 malaria was the most common reason for outpatient department visits in the district for both adults and children. From the total outpatients visits, 37% were diagnosed as malaria broken down as 43% for under-five children and 34% for those over 5 years. Within the district, the District Health Office concentrates on the promotion of correct case diagnosis and early treatment (Mtoto, 1995).

In 1993 a baseline survey conducted by the Zomba district health office in Namasalima community revealed that 35.2% of non sick adults and 37.3% of non sick children under five had plasmodium parasites. In 1994 a baseline survey conducted by the district health office in the same Namasalima community showed that 31.0% of non sick adults and 56.0 % of non sick children under five had plasmodium parasites (Mtoto, 1995).

Health care services in Malawi are provided through free public health facilities at a distance of up to 9 km for most residents. Some private and religious organization hospitals are also available but their fees usually tend to be on the high side for most families. The government policy is to provide a referral hospital with tertiary facilities in each region, one district hospital in each district to act as a referral at district level, a rural hospital with maternity services for every 50,000 people, a health centre for every 10,000 people and a health post with a simple dispensary for every 2,000 people. In all communities, local residents called Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) are trained by the district health office and deployed to communities so that they can advise families during illness and provide health education. The HSAs are an integral part of the health system.

Other players like traditional healers, drug sellers (vendors) and traditional birth attendants also provide health care services at a reasonable cost.

Malaria blood smears to determine malaria parasites are very important in malaria case management. These are not available in most health settings in Malawi due to lack of laboratory facilities in most public health units. The Ministry of Health, therefore, strongly recommends that fevers without another identifiable cause should be treated as malaria if accompanied by one of the following symptoms: headache, chills, shivering, or loss of appetite . In the absence of the requisite laboratory facilities, the World Health Organization recommends that all children who have fever without a known cause in areas of stable transmission of malaria be treated for malaria . The drugs available in Malawi for treating malaria include Fansidar (SP, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine), Halfan (halofantrine), co-trimoxazole, chloroquine, and quinine. By 1991, chloroquine resistance had reached over 80%, and since 1993, SP has been the recommended first line treatment for malaria .

Chapter 2: Malaria and Health Care Seeking Behavior

Patients ordinarily use multiple sources of health care, although self-treatment is their first reaction whenever they are taken ill. In a study conducted in Kenya it was observed that patients are more likely to start with self-treatment at home as they wait for a time during which they monitor progress. This allows them to minimize expenditure in terms of time and money that they would incur if they sought care out side the home immediately. They are more likely to choose treatments available outside the home during subsequent decisions when the signs and symptoms persist. The decisions may include visiting a private health care practitioner, a government health centre or going to a hospital when the situation gets worse. The knowledge of the type of illness involved and its duration, including the anticipated cost of treatment as well as the patient's judgment of the severity of the illness normally influence treatment choice.

It was further observed in the same country that lay people in malaria-affected regions frequently have to choose from many over-the-counter malaria management drugs. This requires them to be able to identify these medications and, at the same time, be in a position to distinguish between such medications. This can be difficult where illiteracy levels are high. Lay people, however, make these distinctions at two levels - age of the patient and then whether he or she has fever, pain or malaria. Sometimes decisions are based on incorrect advice given by friends and relatives which may cause prolonged suffering to the patient while at the same time exacerbating resistance to drugs such as chloroquine and sulfodoxine/pyrymethamine (Fansidar) which are now recommended as first-line drugs for the treatment of malaria in Kenya.

A study conducted in Zomba district in Malawi revealed that some caregivers are likely prefer home treatment irrespective of their proximity to a health facility or their financial situation. Home treatment is more convenient for some, while for others it is the only realistic option for adequate or timely care (Weil et al, 2005).

The study further observed that due to economic, geographic, and other limitations, home medication is often the first treatment option in childhood illness in Malawi. It is also report in the same report that those who do access the health centre, treatment given is often delayed due to travel and waiting periods at health centres which are usually understaffed and about 10 km away. Additionally, health facilities in Malawi often suffer shortages of essential medicine, which result in substandard care and loss of confidence on the part of the patient. In both urban and rural areas, groceries and vendors sell basic medicines at inexpensive prices, and these drugs can be purchased for use at home without prescription.

The study conducted by Weil et al, 2005 also revealed that 45.9% of caregivers’ first response to childhood fever was to treat them at home, while 44.5% of the care givers chose to seek care from a formal health care provider. The study further observed that, overall, less than half of all febrile children received an anti-malarial and that children who lived less than an hour from a health centre were significantly more likely to receive an anti-malarial (OR 1.78, CI 1.22, 2.58) than children who lived more than 1 ½ hours from a health center, regardless of whether the child was treated at the health center or home. Febrile children with seizures and/or loss of consciousness were not more likely to be taken to the health centre than other children in the study (OR 0.94, CI 0.77, 1.15). With respect to prevention, the study concluded that although 25.7% of respondents named bed nets as a malaria prevention method, but that only 16.7% used them in their homes.

The study recommended that to achieve timely and effective care for malaria, caregivers should be given information on home medication and must gain the capability to promptly recognize symptoms of complicated malaria. Local education programs addressing practical methods of malaria prevention and treatment are thus needed to reduce the burden of malaria, especially in areas where health care is inaccessible.

Experience has shown that given the necessary information and reinforcement with simple materials, mothers and other key community members (including drug vendors, traditional birth attendants, and traditional healers) with low levels of education can learn to appropriately recognize and treat malaria. In resource-poor settings where there are limited sources of entertainment, special events like Malaria Awareness Days can be an extremely effective way to provide information and raise awareness about malaria among a large number of people. Community providers, such as traditional birth attendants and traditional healers, are important, highly respected, and trusted individuals who have a definite role to play in maternal and child health (especially in areas where trained health providers are scarce). Their involvement can lend credibility to interventions at community level. Training multiple community members is very critical because it multiplies the opportunities for caregivers to receive accurate information and advice.

Large-scale trials of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) throughout Sub-Saharan Africa have demonstrated that they reduce child mortality in malaria endemic communities. These encouraging results have generated interest in ITNs as a viable malaria control strategy in many malaria endemic countries. However, regular use of ITNs under routine or non-project conditions has been beset with several problems. Although people generally recognize the term 'malaria' they seem to have limited biomedical knowledge of the disease, with respect to its aetiology, the role of the vector, and host response. Convulsions and anaemia are rarely linked to malaria. The people acknowledged a role for ITNs in protecting them from mosquito bites, but not as a malaria prevention tool per se.

Chapter 3: Theoretical Orientation

Medical anthropology is about how people in different cultures and social groups explain the causes of ill health, the types of treatment they believe in, and to whom they turn to if they are confronted with an illness. It is also the study of how these beliefs and practices relate to biological, psychological and social changes in the human organism, in both health and disease. Culture plays a significant role in a person’s understanding and interpretation of illness (Helman, 1994).

People use the term 'culture' in many ways and to mean very different things. In the West, researchers have in the past viewed 'culture' as referring to something that other people have in other parts of the world, without taking into account that every society and community is influenced by culture or cultures (Chakraborty 1991 cited in Eisenbruch 1992). As Clifford Geertz(1973) as cited in Eisenbruch 1992 observes that no human community is 'culture-free'.

The term culture has often been understood to refer only to specific customs, practices, food, or ways of dressing. However, this definition does not adequately cover all elements of culture. Culture is quite broad. Culture is about ways of thinking and living. Culture influences the meanings we attach to issues and events, relationships, and interactions, ways of feeling and experiencing the world. In fact culture is all that a person acquires as a member of society, it is learnt and it is also adaptive.

A useful definition of culture is given by Helman (2000: 2-3) , who defines culture as a:

“set of guidelines (both explicit and implicit) which individuals inherit as members of a particular society, and which tells them how to view the world, how to experience it emotionally, and how to behave in it in relations to other people, to supernatural forces or gods, and to the natural environment. It also provides them with a way of transmitting these guidelines to the next generation - by the use of symbols, language, art and ritual”.

Helman 2000 goes on to say that “to some extent, culture can be seen as an inherent ‘lens’ through which the individual perceives and understands the world that he inhabits and learns how to live within it.” Thus culture dominates our lives; it forms the framework within which we understand and make sense of the world.

Culture can also be defined and described as the underlying beliefs, perceptions, norms and values that are held in common by a group, and that serve as a foundation for social, economic and environmental interactions. The experience of disease and illness are given meaning by culture (Mendelez, 2003). Every culture conceptualizes disease and illness differently. The treatment people seek is influenced by their beliefs and perceptions of what caused their illness. These beliefs and perceptions endure because they have meaning for the members of the group.

Different cultures have unique systems for classifying illness and disease based on perceived symptoms. A symptom is any subjective evidence of organic change or changes in some bodily or mental state that are felt by the patient. According to Mendelez, 2003, “symptoms can be warning signs that organic change (illness) is occurring”. In biomedical terms, signs are what a clinician finds after examining the patient. The symptoms, in many cases, differ in severity, duration and intensity.

The term "disease" generally signifies any organic illness. Rene Dubos (cited in Mendelez 2003) defines disease as “any departure from the state of health,” and health as “a state of normalcy free from disease or pain" (1965: 348). Disease can be measured to determine pathological condition of the body. In contrast, illness is more subjective, a feeling of not being in balance or healthy. Thus illness may, in fact, be due to a disease. This explains why in some societies not all diseases are perceived as illness.

Beliefs and perceptions of symptoms and illness are related to culture, while disease usually is not. For example, the study conducted by Mendelez 2003 in the Dominican Republic concluded that illness is believed to occur when one's system is out of balance. Thus, according to Mendelez, 2003 within Dominican society there exist unique and personal ways of formulating causes of illness, which contrasts with conventional medical diagnosis, as well as the beliefs and perceptions of other cultures.

Different cultures embody strategies for coping with and healing illness and disease. Interpreting the cultural context of symptoms and illness requires understanding cultural beliefs and perceptions, and meanings that underlie a social system which constitutes the ‘lens’ through which individual societies explain illness. Culture influences how people communicate to others what they feel and how they cope with illness (Helman, 2000). Symptoms and illnesses are painful experiences in themselves, but they become more painful when the sufferer is unable to communicate how he or she feels. Helman writes that “the process of ‘becoming ill’ involves "…both subjective experiences of physical or emotional changes and, except in the very isolated, the confirmation of these changes by other people” (2000:85).

In the same study conducted by Meléndez 2003 in the Dominican Republic it was revealed that, “Parkinson’s disease, linked to pesticide exposure, is considered a spiritual evil, a malefic and threatening destiny that the diseased person must endure unless he exorcises the evil”.

Meléndez 2003 further observes that the hot/cold theory of diseases survives in the study region. This hot/cold theory traces its roots to the Aristotelian system of humors, which were hot or cold, wet or dry. Internal organs, illness, foods, and liquids are classified as being "hot" or "cold," and good health depends on maintaining a balance or equilibrium of hot and cold (Helman, 2002; Brady, 2001; Strathern and Stewart, 1999 cited in Meléndez 2003). A "cold" ailment calls for "hot" herbs and foods to restore the balance, and vice versa. According to Meléndez, temperature is not the key factor in the classification scheme; ice is "hot" because it can burn, and tea, such as “tilo” in the Dominican culture, though served hot, is "cold" and is often used by locals to treat "hot" ailments.

In Malawi, a study conducted by Bisika et 1999 showed that women used to treat eye problems in children using ‘cold’ breast milk. Breast milk was considered could if the woman was still observing post-partum abstinence .

There are also differences in the way patients and healers explain and understand illness. Arthur Kleinman (1978), observes that psychiatrist and medical anthropologist, uses the term 'explanatory model' to explain that the patient and the healer may have very different conceptual understandings of the nature of the illness, its cause, and its treatment. The disturbing experiences of a returning soldier, for example, may be seen by a psychiatrist as symptoms of a different condition while to the soldier and his or her family, these symptoms may be signs that vengeful spirits of the innocent people they have unjustly killed may be disturbing them. Whereas the psychiatrist may recommend some form of therapeutic intervention, the family may believe a purification ritual to appease the spirits to be the most effective remedy. The psychiatrist and the family hold different explanatory models of the problem and conflict may arise when communication across these different models does not occur .

According to Hodgson, 2000, cultures, in making sense of illness, have clusters of explanatory models, the ‘lenses’ through which cultures perceive and understand illness. As presented by Arthur Kleinman (1980), the term refers to interpretive notions about an episode of sickness and treatment that are employed by all those engaged in the clinical process. Importantly, both carers and patients utilize explanatory models extensively. In particular, explanatory models address 5 aspects of illness:

The cause of the condition;

The timing and mode of onset of the symptoms;

The pathophysiological processes involved;

The natural history and severity of the illness; and

Appropriate treatments for the condition.

According to Kleinman, non-professional explanatory models tend to be idiosyncratic, changeable, and heavily influenced by cultural and personal factors. In a discussion of explanatory models, Helman (2000) suggests that medical explanatory models are 'based on single, causal chains of scientific logic'.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the role of explanatory models of illness that are based on subjective experience and the prevailing cultural context, as providing a valuable tool in helping to construct meaning, and make sense of the world (e.g. Weiss, 1988; Farmer, 1994) .

In our communities people revert to both cosmopolitan (biomedical) and traditional folk medicine. The Table 1 below summarizes the major differences between the two.

Table 1: Biomedical versus Traditional Folk Medicine

BIOMEDICINE

|

TRADITIONAL FOLK MEDICINE |

Looks at isolated disease agents, which it attempts to change and control. |

Holistic, treats the person rather than the disease. |

Separate physical illness from emotional and psychological illness. |

Mind and emotions are one. |

Starts with the symptom and then searches for the underlying mechanism - a precise cause for the disease. |

Treats "patterns of disharmony" that describe a situation of imbalance in the patient. |

Heavily dependent on quantifiable methods such as x-rays scans to make a diagnosis. |

Uses both a clinician as well as the subjective symptoms reported by the patient to heal. |

Uses diagnostic tools to come up with a quantifiable description of the illness. |

Looks at relationships more than causes.

|

Sources: Jones and Polk, 2001: Brady 2002l Adler 1999, 2000, 2001 (cited in Meléndez 2003)

There are, indeed, different ‘lenses’ through which one can view illness and problems in a particular society. The etic and emic views have, however, been distinguished. Etic and emic perspectives refer to whether one adopts an 'outsider' or 'insider' view of an illness or problem in a community.

The etic perspective imposes a way of viewing the world on the illness as an outsider. Usually this is a Western, biomedical view that tries to make an illness fit a prescribed biomedical category. Behaviour and illnesses are examined from a position outside the social or cultural system in which they take place.

The emic approach is the 'insider' perspective, in which the world-view of the people who are ill or distressed is adopted. The cultural and social system in which the people find themselves is seen as central to understanding the illness (Berry et al. 1992 cited in Meléndez, C. 2003) .

Criticism has been expressed of the cultural approaches to providing psychosocial assistance : Such criticism include:

- Cultural approaches provide information about one specific community that cannot be generalized to other communities. It has been argued that this approach has limited practical value as the information gathered cannot be applied to inform a broader approach. Thus, studies that use the cultural approach do not have external validity.

- There is a danger that local culture and local resources may be romanticized and seen as the solution to all problems. This is often not the case as resources have been destroyed, healers may not be available, and the performing of rituals may not be possible in locations to which people have been displaced. There is a need to be aware of not romanticizing local culture.

- Some advocates of a cultural approach view 'culture' as static entities rather than as constantly changing dynamic systems. There is a danger that people seek to identify certain characteristics of cultures (e.g., 'Cambodians believe in spirit possession') without taking into account variation within the population, as well as the changing nature of beliefs, lifestyles, and ways of thinking.

- Issues of power between individuals and groups are present in all communities. The emphasis on taking local practices as a starting point may contribute to maintaining unequal power structures in communities.

Chapter 4: Purpose and Study Objectives

The purpose of this study was to collect information on local ethnomedical beliefs, household illness management practices, care-seeking for sick children, health practitioners’ beliefs and practices related to malaria and sources of information and advice for care givers. This information is required by case managers in the course of providing care for the seek children.

The study provides a description of local beliefs and practices about common childhood illness that involve fever, including a discussion of the illnesses recognized by families which overlap with clinically defined malaria; the signs and symptoms families associate with these illnesses; beliefs about the causes and severity of these illnesses, signs and symptoms; and perceptions about appropriate treatment of these different illnesses, including both home treatment and care-seeking.

In addition to describing local beliefs about childhood illness and its management, the study tries to identify other factors that affect home care and care-seeking practices for children with malaria, such as household dynamics and economic conditions.

The specific objectives of the study were to:

Describe community beliefs and practices related to malaria, and identify factors that facilitate or constrain prompt care-seeking from a trained health practitioner when children present signs suggestive of malaria. These factors may include, among several others, economic, geographic, social and cultural impediments that prevent families from seeking timely and appropriate care; and

Make recommendations as to how to improve recognition and treatment of childhood malaria at community level. These may include ways to improve families’ recognition of the signs and symptoms suggestive of malaria; ways to encourage prompt care seeking from a practitioner trained in standard malaria case management; ways to improve malaria case management by public and private health practitioners, including pharmacists, drug vendors and traditional healers, and ways to improve compliance with multi-dose anti-malaria therapy.

Chapter 5: Methodology

The study was conducted using the “Guidelines for Conducting a Rapid Ethnographic Study of Malaria Case Management” developed by World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (WHO/TDR).

Study Site

The field study was conducted in Zomba District in the South of Malawi. Zomba District has a population of about 600,000 according to the 1998 Malawi Housing and Population Census. The actual study site was Namasalima which is 32 km north of Zomba town. Namasalima is a community distinguished by irrigation rice farming and has 11 villages with a well functioning health centre. The area has a population of 12,231 and is located near an inland draining lake called L.Chirwa.

The main economic activities in the area include rice farming and fishing. The ethnic groups are Nyanja and Yao but the former dominates. Namasalima has a reasonably staffed health centre located more or less in the middle. It is also 17km from Domasi Rural Hospital and about 32 km from the Zomba Central Hospital. In addition there are some groceries and canteens which sell pharmaceuticals. Some traditional healers also exist in this village.

Namasalima is an area of both ecological and epidemiological importance. It was specifically selected for this study because it serves like a control site for the Likangala impregnated bed net programme. The absence of such an intervention and its irrigation rice farming activities makes malaria a common public health problem and thus it was important to study malaria case management under these conditions.

Study Design

A community based study design was employed in this ethnographic study of malaria case management. This means that Interviews were conducted with respondents from a defined area that is identifiable as a community rather than from a large geographical area, as is common with survey research. The main reasons for employing a community based study design were:

- Primary health care services are usually organized at the community level, and therefore families’ decisions about where to seek care are made within this community context. Furthermore, focusing on a single community allows the investigator to look at the way in which different factors affect health seeking practices in a community setting;

- Working in a single community gives the investigator more opportunities to observe behaviour and understand local conditions than is the case with survey researchers who move rapidly from one community to another.

Sampling and Data Collection

Data collection was conducted in two phases using a field study. A number of study instruments and techniques were used with different categories of respondents. This was done to ensure that data collection methods were triangulated. When there is consensus from different data collection instruments administered to different respondents the investigators can accept the results with even more confidence.

In Phase 1, a total of 15 key informants were interviews during the initial interviews but two were lost in the subsequent follow-up interviews. The key informants were selected in consultation with the Health Surveillance Assistant from the health centre and other key informants who included chiefs, and traditional healers. When a name of an individual was proposed as a possible key informant, a social scientist went to that individual to assess that person’s willingness and suitability to be a key informant. Three to Four names were proposed per village and since one village was inaccessible the research team ended up with 36 names from 10 villages. When these potential key informants were visited, only twenty were eligible to become key informants. Fourteen of the potential key informants were dropped on the basis of availability while two were dropped on the basis of unwillingness to share information with the study team.

From the remaining twenty eligible key informants, 15 were selected on the basis of geographical location, services they provide to the community, distance from the health centre and size of the village they come from.

The interviews with key informants involved free listing and open-ended interviews about locally recognized illnesses, signs and symptoms. In addition six key informants, one traditional birth attendant and three respondents who participated in Phase 2 interviews were shown a video containing clips of sick children in order to assess the relationship between illness terms mentioned by the informants and the physical signs and symptoms of interest. The video interviews were conducted at end of Phase 2 because the research team received the video equipment late due to logistical problems.

In this phase 23 women with children under-five were also interviewed for the past illness episodes in their children. These women were selected systematically from six randomly selected villages. If in the selected household there was no child under five or no illness episode in the preceding 2-4 weeks, the next household in succession was selected. This process was repeated until a respondent was identified.

During the current episode interviews 41 mothers and primary care takers were interviewed. To find the currently ill children a mobile clinic was mounted in collaboration with the District Health Office. The clinics were announced in the preceding three days and mothers and care-takers were asked to bring children

African Union Commission. 2005. An African Common Position on the Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Malawi Government Ministry of Health and Population, January 2002. Malaria Policy, Specific Policy Statements, vii

20th WHO Expert Committee Report on Malaria May 2001. Management of Uncomplicated Malaria, ch 5.1

Malawi Government Ministry of Health and Population, January 2002. Malaria Policy, Specific Policy Statements, 11

Nyamongo, IK. 2002. Health care switching behaviour of malaria patients in a Kenyan rural community. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Feb;54(3):377-86.

Nyamongo, IK. 1999. Home case management of malaria: an ethnographic study of lay people's classification of drugs in Suneka division, Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 1999 Nov;4(11):736-43

Nathaly Herrel , Diana DuBois, 2004. Improving malaria case management in Ugandan communities: Lessons from the field. Community-Based Primary Health Care Working Group

IH Section, APHA – November 6th, 2004

Philip B. Adongo, Betty Kirkwood and Carl Kendall. 2005. How local community knowledge about malaria affects insecticide-treated net use in northern Ghana. Tropical Medicine & International Health Volume 10 Issue 4 Page 366 - April 2005

Bisika,T., Courtright, P, Thakwalakwa,C. 1999. An exploratory study of traditional eye medicine and Biodiversity in Malawi. Centre for Social Research: Zomba.

Hodgson, I. (2000) - Culture, meaning and perceptions: explanatory models and the delivery of HIV care. Abstract MoPeD2772, XIIIth International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, July 14th-19th.

Hodgson, I . 2005. An ethnographic investigation into the culture of health care workers involved in the care of people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). University of Bradford, and South Bank University

Honwana, A., 'Non-western Concepts of Mental Health'. In M. Loughry and A. Ager (eds), The Refugee Experience. Psychosocial Training Module (rev. edn). Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre. 2001 http://earlybird.qeh.ox.ac.uk/rfgexp/rsp_tre/student/nonwest/toc.htm (accessed on July 25, 2005).

Nader, K., Dubrow, N., and Stamm, H., Honoring Differences: Cultural Issues in the Treatment of Trauma and Loss. Philadelphia: Bruner/Mazel, 1999.

Nordstrom, C., A Different Kind of War Story. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997

Swartz, L., Culture and Mental Health. A Southern African view. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1998.

who were sick. Two mobile clinics were organized: the first one took place in the second week of a malarias months of January in Kalinde Village while the second one took place in Matewere village in the forth week of January. Both clinics were starting at 09:00 hours in the morning and continued until late in the afternoon.

At these clinics there was a physician, a laboratory technician and a paediatric nurse who knew the area very well. About 200 children were brought to each of these clinics. The social scientist was the first one to see each child and interview the mother. The mother was asked about the child’s problem and if fever or any other symptom suggestive of malaria was mentioned then the social scientist would refer the mother to a research assistant for an interview.

These interviews were semi-structured and research assistants were allowed to ask additional questions. At this stage the paediatric nurse would take body temperature and at the end of the interview the nurse would also collect a blood smear to be analyzed for malaria parasites and anaemia. After this whole process the physician conducted a complete medical examination and treated the child accordingly. All medicines were provided free of charge. The children who did not present signs and symptoms suggestive of malaria were referred directly to the physician and their body temperature and blood smear were not collected.

A total of seven health practitioners were also interviewed in Phase 1. These were selected considering their geographical location, illnesses they see and the type of practitioner they are. One storekeeper, one sooth sayer, two traditional healers (one next to the health centre and the other one a chief in a remote village far from the health centre), a nurse, a health assistant and medical assistant providing care at the only public health centre in the community were thus interviewed.

In addition, four drug sellers (shop keepers) were presented with a hypothetical illness case. Here a local woman (aged 34 years) was hired and given money to visit the drug sellers and tell them that she had a two year old daughter who has had fever for three days and was not eating. The local woman would then ask the drug seller the appropriate type of medicine that she should buy without mentioning the name of the medicine herself. Immediately after this encounter the woman was interviewed by the social scientist about her experienced to avoid recall bias and the medication bought was inspected.

All drug sellers who had anti-malarials were visited. Since one of them was situated in the market he was visited on the market day as well as on a normal day. Table 2 below summarized Phase1 activities.

Table 2: Summary of Phase 1 Methodology

Activity |

Data Collection Technique |

Interviews with 15 Key Informants |

Open-ended interviewing and free listing of illnesses and signs and symptoms (including interviews about past illness episodes) |

Interviews with 13 key informants (from the 15 original key informants) |

Paired comparisons of illnesses |

Interviews with selected 6 key informants from the 13 and 4 mothers |

Assessing the relationship of local terms to physical signs and symptoms using a video tape |

Interview with 23 mothers about past illness episodes involving fever |

Narratives of past illness episodes including narratives with mothers whose children died as a proxy for personal anecdotes and verbal autopsy for mothers whose children had died |

Interviews with 41 mothers of children who were currently ill |

Semi-structured interviews of current cases with blood smear analysis, blood count and temperature measurement |

Interviews with a representative sample of 7 health practitioners |

Semi-structured interviews |

Presentation of hypothetical illness case to 4 drug sellers (simulated case) |

Presentation of hypothetical case and in depth interviews. |

The purpose of Phase 2 interviews was to systematically explore the degree to which there is consensus in the community around the key aspects of the findings from key informant interviews. In addition it was envisioned that these interviews would ensure that all potential sources of variability have been identified.

In this phase a total of 76 mothers were interviewed. To select these women the study area was stratified by village, that is, each village formed a distinct entity. Six villages were then purposively selected paying particular attention to ethnicity, distance from health facility and religion. From these villages a systematic sample of the 76 mothers was drawn.

A structured questionnaire was developed which was initially pre-tested with key informants. The questionnaire had four sections. The first was on matching illnesses with symptoms, the second was on severity rating of illness symptoms, the third was on forced choices of health practitioners and the fourth was on household inventory of medicines. Each respondent answered all questions from all sections. Table 3 below summarizes Phase 2 activities.

Table 3: Summary of Phase 2 Activities

Activity |

Data Collection Technique |

Pre-testing of structured interviewing procedures with key informants, then interviews with a representative sample of 76 mothers from the community who had children under the age of 5 years |

Matching of Illnesses and symptoms

Severity rating of illnesses and symptoms

Forced choice of health practitioners

Inventory of medications in the home |

Throughout this study participant observation was used to supplement some of the information. The intensive field work took 4 months due to some delays, however, participant observation continued for an extra two years. This component was eased when the research assistant ended up getting married to a young lady who was from the area. The principal investigator was also involved in buying and selling of rice from the same area for the 2 years.

The principal investigator was also from one of the ethnic groups present in the area which facilitated easy understanding of the cultures some of which were not even known to him in advance.

Data Analysis and Report writing

Content analysis of the qualitative information was done manually using carefully designed matrices. Report writing was on going and a lot of revisions were necessary as more and more information became available.

All the study results were summarized in different tables depending on the subject of interests.

Ethical Considerations

Since physical harm to subjects is very rare in anthropological research, the main ethical considerations when dealing with human subjects are privacy, informed consent and confidentiality. Before embarking on this study the author had to undertake a course on Human Participants Protection Education for Research Teams sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (http://www.nih.gov). The course mainly covered the following aspects:

Key historical events and current issues that impact guidelines and legislation on human subject protection in research;

Ethical principles and guidelines that should assist in resolving the ethical issues inherent in the conduct of research with human participants;

The use of key ethical principles and federal regulations to protect human participants at various stages in the research process;

A description of guidelines for the protection of special populations in research;

A definition of informed consent and components necessary for a valid consent;

A description of the role of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the research process; and

The roles, responsibilities, and interactions of federal agencies, institutions, and researchers in conducting research with human participants.

Privacy

All observations were conducted with full privacy along with the interviews. The interviews were arranged in such a way that the respondent was neither seen nor heard by other people at the respondent’s convenient time.

Confidentiality

Names of respondents were kept confidential and were not linked directly to the responses. The responses were labeled by respondent household code. All information collected during the interviews will be treated as confidential at all times.

Informed Consent

The purpose of the study was explained to the participants and the use of visual materials was also clarified to the respondents. Interviews were only conducted with those respondents who agreed. The study subjects were informed that they were free to withdraw at any time. No inducements were used as this would constitute “coercion”.

Beneficence

The principle of beneficence was adhered to. All respondents with children who had malaria parasites were treated using the existing treatment guidelines. The Ministry of Health participated at this stage. The findings of this study will also be of benefit to the whole community since it will improve communication between the health practitioners and the community.

Ethics Review Approval

The proposal was submitted to National Health Sciences Research Committee of the Malawi Government for ethical review. An approval was received in December, 1995 (Ref document Malawi/Gov/ 05/5G).

References

Adongo, P. Betty Kirkwood and Carl Kendall. 2005. How local community knowledge about malaria affects insecticide-treated net use in northern Ghana. Tropical Medicine & International Health Volume 10 Issue 4 Page 366 - April 2005.

Adongo, P. and Patricia Hudelson, 1995. The Management of Malaria in Young Children in Northern Ghana: A Report of a Rapid Ethnographic Study. Navrongo Health Research Center, Navrongo, Ghana; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; WHO, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, Geneva, Switzerland (October 1995).

Baume, C. 2002. A Guide to Research on Care-Seeking for Childhood Malaria, SARA Project, AED, Washington, DC; BASICS II Project, Arlington, VA; USAID, Washington, DC (April 2002).

Bauwens, Eleanor E., editor. 1978. The Anthropology of Health. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby.

Bisika, T. 1998. A Process Evaluation of the Insecticide Impregnated Bed net Project in Zomba District. Zomba: Ministry of Health District Health Office.

Brady, Ericka, editor. 2001. Healing Logics Culture and Medicine in Modern Health Belief Systems. Utah State University Press.

Cartwright, Elizabeth. 1998. Malignant Emotions: Indigenous Perceptions of Environmental, Social and Bodily Dangers in Mexico. University of Arizona (Ph.D. Dissertation).

Clark I, Whitten R, Molynuex M, and Taylor T, 2001. Salicylates, nitric oxide, malaria, and Reye’s syndrome. Lancet 357:625-627

Dalmau, Felipe. 1978. Obatalá, Changó y Ochún: Elementos Espirituales de la Santería. New York, NY: Colección Destino.

Dawson,S., Lenore Manderson and Veronica L. Tallo. 1993.A manual for the use of focus groups. 1993.

Dubos, R. 1965. Man Adapting. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Farmer, P. (1994). “Aids-Talk and the Constitution of Cultural Models.” Social Science & Medicine 38(6): 801-809.

Eisenbruch, M. 1992. Cultural and anthropological studies

http://216.239.35.100/search?q=cache:lzCNbuJucm8C:www.dinarte.es/salud-mental/pdfs/Eisenbruch-From%2520PTSD%2520to%2520cultural%2520bereavement.pdf+Maurice+Eisenbruch+cultural+bereavement&hl;=en&ie;=UTF-8

Foster, GM, Anderson, BG. 1978. Medical Anthropology. New York, Wiley.

Gove, S., Pelto, G. 1994. Focused Ethnographic Study of Acute Respiratory Infections. WHO, Geneva.

Halima Abdullah Mwenesi. 1994. Focused Ethnographic Study of Malaria: Field-Testing of a Rapid Assessment Manual, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya (November 1994) 83 pp.

Harrison LH, Moursi S, Guinena AH, Gadomski AM, el-Ansary KS, Khallaf N, Black RE, 1995. Maternal reporting of acute respiratory infection in Egypt. Int J Epidemiol 24(5):1058-63

Helman, C. G. 1995. Culture, Health and Illness. Heinemann, London.

Herrel, N, Diana DuBois, 2004. Improving malaria case management in Ugandan communities: Lessons from the field. Community-Based Primary Health Care Working Group IH Section, APHA – November 6th, 2004

Hudelson, P. 1995. "Guidelines for Conducting a Rapid Ethnographic Study of Malaria Case Management." Second Fieldtest Version. Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR).

Hudelson, P and Halima Abdullah Mwenesi. 1995. A Protocol for a Focused Ethnographic Study of Malaria., London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; WHO, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, Geneva, Switzerland; Kenya Medical Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya (November 1995) 101 pp.

Kleinman, A. 1980. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley, University of California.

Kofoed PE, Lopez F, Abay P, Hedegaard K, and Rombo L, 2003. Can Mothers be trusted to give malaria treatment to their children at home? Acta Tropica 86 :67-70

Landy, David. 1977. “Role Adaptation: Traditional Curers under the Impact of western Medicine.” In Culture, Disease and Healing. Editor: David Landy. Pp. 468-480.

Layne, SP.2005. UCLA Department of Epidemiology, "Principles of Infectious Disease Epidemiology / EPI 220 (www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/layne/Epidemiology220/07.malaria.pdf) accessed on August 10, 2005.

Leach, E. 1982. Social Anthropology. Glasgow, Fontana.

Malawi Government Ministry of Health and Population, January 2002. Malaria Policy, Specific Policy Statements

Marsh V, Mutemi W, Muturi J, Haaland A, Watkins W, Otieno, Marsh K, May 1999. Changing home treatment of childhood fevers by training shop keepers in rural Kenya, Trop Med and Int Health 5,4:383-389

Meléndez, C . 2003.Culture, Health and Environment: A Multidisciplinary Evaluation of Communities Exposed to Pesticides in the Constanza Region, Dominican Republic. Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, NY.

Mtoto, G. 1995. A Report of the Likangala / Namasalima Bednet Project Baseline Survey. District Health Office, Zomba.

National Statistics Office, 1998 Malawi Population and Housing Census

Nyamongo, IK. 2002. Health care switching behaviour of malaria patients in a Kenyan rural community. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Feb;54(3):377-86.

Nyamongo, IK. 1999. Home case management of malaria: an ethnographic study of lay people's classification of drugs in Suneka division, Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 1999 Nov;4(11):736-43

Rubel, AJ. 1977. The Epidemiology of Folk Illness: Susto in Hispanic America. In Landy, D. (Ed), Culture, Disease and Healing: Studies in Medical Anthropology. New York, Macmillan.

Simpson, G. E. 1971. “The Belief System of Haitian Vodun.” In Peoples and cultures of the Caribbean: an anthropological reader. Edited and with an introduction by Michael Horowitz. Garden City, NJ: Natural History Press.

Strathern, A and Pamela J. Stewart. 1999. Curing and Healing: Medical Anthropology in Global Perspective. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Tavrow, P. 1994. The Evaluation of Drug Revolving Funds in Mbalachanda. Centre for Social Research, Zomba.

USAID 2000. Malawi Health and Demographic Survey, Summary of findings, Zomba District, National Statistics Office, 2-4

Weil,Anna, Thomas Bisika, Clive Shiff. 2005. Management of fever by head of household in children 12 and under in Zomba District, Malawi: Health Center or Home Treatment. Draft Report, Unpublished.

Weiss, M. G. (1988). “Conceptual models of diarrhoeal illness: conceptual framework and review.” Social Science and Medicine 27(1): 5-16.

WHO/TDR. 1999. Rapid Assessment: Health Seeking Behavior for Severe and Complicated Malaria. WHO, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), Geneva (September 1999) 24 pp.

WHO/TDR. 1999. Rapid Assessment: Recognition of Illness Symptoms for Severe and Complicated Malaria. WHO, Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), Geneva (September 1999) 28 pp.

WHO/TDR. 1999. Using Ethnographic Research to Improve Malaria Management in Young Children. WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. WHO/TDR, USAID/AFR/SD, Washington, DC (July 1999) 8 pp

WHO/TDR. 1995. The malaria manual Guidelines for the rapid assessment of social, economic and cultural aspects of malaria. By Irene Akua Agyepong, Bertha Aryee, Helen Dzikunu and Lenore Manderson

WHO. 2001. 20th WHO Expert Committee Report on Malaria May 2001. Management of Uncomplicated Malaria, ch 5.1