| Motlhalosi Tlotleng Doctor of Business Administration Business Administration and Finance Botswana |

Mmoloki Moreo Master of Management and Leadership Educational Management and Leadership Botswana |

Kamila De Oliveira Barros Bachelor of Science Psychology Brazil |

Hugo Patricio Muñoz Aravena Bachelor of Science Psychology Chi |

William Diaz Henao Doctor of Business Administration Business and Finance Colombia |

Burbano Rosero Adriana Rocio Bachelor of Education Preschool Education Ecuador |

| Phineas Londiya Nhlanhla Magagula Doctor of Philosop hy Business Administration Eswatini |

Janice Firebrand Johnson Master of Arts Diplomacy and World Affairs Ghana |

Bernadette Touwendsida Nikiema Master of Science Psychology Ghana |

Lilian Beatriz Hernández Guerra Doctor of Legal Studies International Legal Studies Guatemala |

Rozana Chand Bachelor of Science Project Management Guyana |

Jose Abraham Alvarez Martinez Bachelor of Business Administration Business Administration Honduras |

| Josué Daniel Crespo Elliot Bachelor of Science Industrial Engineering Honduras |

Navit Shahar Nirhod Bachelor of Arts Psychology Israel |

Yaman Jaad Msarwe Bachelor of Education Education Israel |

Terron Hewitt Bachelor of Accounting Accounting Jamaica |

Isabelle Jerop Kandagor Doctor of Philosop hy Sustainable Telecommunications Kenya |

Roxanny A. del Pilar Moulas Vargas Bachelor of Science Psychology Mexico |

| Jose Juan Ruiz Ruelas Bachelor of Science Civil Engineering Mexico |

Emmanuel Ucheoma Ojobah Bachelor of Science Psychology Nigeria |

Nwonye Emmanuel Ifebuche Doctor of Business and Economics Project Management Nigeria |

Christopher Jeremiah Abimiku Doctor of Philosop hy Business Management Nigeria |

Edem Chigozie Eucharia Doctor of Science Social and Human Development Nigeria |

Usman Kolawole Aleshinloye Doctor of Management Project Management Nigeria |

| Francis Ezike Okagu Master of Business and Economics Project Management Nigeria |

Farzin Shahrokhi Doctor of Psychology Psychology Norway |

Jesus Martin Pacheco Rivera Bachelor of Science Electromechanical Engineering Panama |

Arlito P. Cuvin Bachelor of Science Architecture Philipp ines |

Victoria Cupet Doctor of Education Education Romania |

Francio Frans Buys Doctor of Science Public Health South Africa |

| Mohammed Ajak Abdalla Arke Bachelor of Public Administration International Relations South Sudan |

Mathokoza Mntambo Bachelor of Science Computer Science Swaziland |

Kerim Çolakoğlu Bachelor of Science Mechanical Engineering Türkiye |

Selim Çolakoğlu Bachelor of Science Mechanical Engineering Türkiye |

Agnes Kabanda K Doctor of Project Management Project Management Uganda |

Mauricio Adrian Kanigina Cap Bachelor of Science Psychology Uruguay |

| Jenipher Mhlanga Bachelor of Science Psychology US A |

Atriel Arias Bachelor of Science Psychology and Human Development US A |

Erminda Eli Pacheco Caseres Bachelor of Business Administration Business Administration US A |

Fahimeh Raoufi Doctor of Science Biology US A |

Michel Peña Del Rosario Bachelor of Science Psychology US A |

Duviel Rodriguez Doctor of Philosop hy Psychology US A |

| Devan Lane Pope Doctor of Arts English Literature and Language US A |

Edson Rivera Román Bachelor of Science Architecture US A |

Rosemary N. Situmbeko Kabwe Doctor of Philosop hy Health Care Administration Zambia |

Rosemary N. Situmbeko Kabwe Doctor of Philosop hy Health Care Administration Zambia |

||

Christopher Roger Williams

Christopher Roger Williams Christelle Katumba Shimbi

Christelle Katumba Shimbi Anu Joseph

Anu Joseph Fadi AbuAita

Fadi AbuAita

We observe every day the

relationship and development

of nations and ask

ourselves: Where are we going

as a society?

The world we know is made

up of our solar system in

which our planet Earth is. In

turn, our planet Earth is made

up of flora, fauna and human

beings; with all of us we build

our social world. We live from

what our planet produces and

in our social world we create

science. We develop science

through formal education.

What world are we in? What

do we have to learn? Where

is science going? Every day

it seems that we have new

answers. The answer to the

first question, at first glance,

seems to be simple. We are in

a world where nature is not

seen to be protected. Nature

is the source of life for flora,

fauna and the human species.

We have created an unsustainable

development:

extraction of non-renewable

products, dependence on fossil

fuels, and little care for natural

resources, such as water.

It is maintained, as in the

United Nations-UN, that

global warming can’t rise

more than 1.5 Celsius. This is

the result of the United Nations

Conference on Climate Change-Conference of the

Parties (COP21), held in Paris

on December 12, 2015, and

whose agreement was signed

by 196 countries on November

4, 2016. At this Conference,

the countries committed to

reviewing them every 5 years.

At COP26, held in Glasgow,

Scotland, UK, the same agreements

for climate change were

also met, but the same: they

aren’t complied with for one

reason or another.

In the Conference of the

Parties of the UN-COP27, held

in Egypt, in November 2022, it

deals with the same theme of

the Paris Agreement, where the

countries sign, but the changes

are offered by many, until

2050, because they say no to be

able to switch energy from oil

and coal as quickly as needed.

Let’s see now what education

is. Education has the two

known aspects: informal education

and formal education.

Informal education is the

cultural values that we learn

from coexistence. Formal education

is what States organize

based on what they want about

human being will be: it is

structured based on the needs

of nations to develop culture,

economy, and human values.

There are Open and Closed

Curricular Designs. At Atlantic

International University (AIU),

where you are studying, you

have both modalities of Curricular

Design.

In an Open Curriculum

Design, the student can choose

the disciplines that are of

interest. In a Closed Curricular

Design, the institution offers

the study plan to follow.

In the Open Curricular

Design, also in the Closed Curricular

Design the institution

chooses its Philosophy and its

Policy. Philosophy is what the

institution believes in: learning,

society, social relations

and ultimate goals of education.

Policies are the rules by

which the institution is guided in each of its departments.

Formal education can be

face-to-face, which means

attendance at facilities with

teachers who, through appropriate

resources, show students

the procedures to follow or

review the activities developed

by them. In formal education

we have psychological and

pedagogical methods that seek

better student learning.

Nowadays there is a strong

development of modalities

to learn more every day: we

are talking about virtual or

online education. In any case,

students: have to use virtual or

online media even if they are

in face-to-face education, to

carry out all the activities. Students

in face-to-face classes

also have the use of virtual or

online media as subjects.

Regarding the third question

of “Where is science

going?” what we notice is that

every human being, nowadays,

thinks he or her knows

everything. In addition, all the

falsehoods that one can imagine

are published through the

Platforms. Those who are unaware

of the existing problem

regarding the dissemination of

what is believed to be scientific

repeat falsehood and a half.

Science, nowadays, is more

popular but you have to know

where to look for reliable

information. One of the functions

of universities is the dissemination of science. It

also joins this way of working

with the truth, which

must correspond to a theory

already proven and accepted

by the international scientific

community.

Nowadays society is very

confused with what freedom is:

everyone does and says what

comes to mind, which is why

we live in chaos. We say to be

in chaos because:

a While some enjoy extreme

abundance, others die of

hunger.

b Some maintain scientifically

that it is necessary to regulate

the heat on the planet

while others deny it.

c Some want to continue

producing energy from oil

while others deny that it is a

problem of survival.

d Some want production to be

based on green energy and

others want fossil fuels such

as coal.

e Science is done with procedures,

theories and laws

agreed upon by the international

scientific community it

is not saying what you want.

f There must be respect for the

other while others are only

concerned with their benefit

regardless of what may happen

to others.

g Some have the right to education

while others barely

reach basic studies.

We ask ourselves: where are the values? Where the respect

is for the other? The theories

are still valid over time and

present elements on which you

can continue working.

Speaking of chaos, here is

the theory: Where does chaos

come from and how situations

are resolved in the face of it.

Ilya Romanovich Prigogine,

Moscow, January 25, 1917-

Brussels, May 28, 2003. He was

naturalized Belgian in 1949. He

studied Chemistry at the Free

University of Brussels, also at

the same institution he studied

Physics. He received the 1977

Nobel Prize in Chemistry for

his work on the Theory of Dissipative

Structures.

Prigogine said: “Our world

is a world of change, exchange

and innovation. To understand

it, a theory of processes,

lifetimes beginnings and ends

is necessary; we need a theory

of qualitative diversity, of the

appearance of the qualitatively

new. (Prigogine 2009, pp . 70-71).

This was said by Prigogine

working at the beginning of

this century. We know that it

has cost a lot of effort in the

field of research to introduce

the qualitative. How is it possible

to move from chaos to balance.

According to Prigogine:

“We have called the order

generated by the state of nonequilibrium

“order by fluctuations”.

Indeed, when, instead

of disappearing, a fluctuation increases within a system,

beyond the critical threshold of

stability, the system undergoes

a profound transformation, it

adopts a completely different

mode of operation, structured

in time and space, functionally

organized. What then emerges

is a process of self-organization,

what we have called “dissipative

structure”. (Prigogine,

2009, p. 89).

We go from chaos, which is

the non-equilibrium of a system,

to the search by the same

system for its equilibrium.

Nowadays society, which is

in chaos, where any thought is

true, where it doesn’t matter

what happens with the way

nature is used, where values

don’t matter, where respect for

others are not necessary: you

will find your own balance.

We don’t know how long it

will be necessary for the system

which is the current world

with education, science and the

values that the human being

has to find the balance which

will be peace to build a world

and to build in them a better

human being where life is for

growth instead of the destruction

we live.

Take advantage of your

time to build.

Take advantage of your

study time at AIU to be

and make a better world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. ONU-Acuerdo de París COP21. París 2015

Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/es/climatechange/paris-agreement | ONU

COP21. París 2015 | Retrieved from: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/es/politica-

exterior/clima-y-medio-ambiente/la-lucha-contra-el-cambio-climatico/

conferencia-de-paris-o-cop21/ | Prigogine, I. 2009. ¿Tan solo una ilusion?

Barcelona: Tusquets Editores.

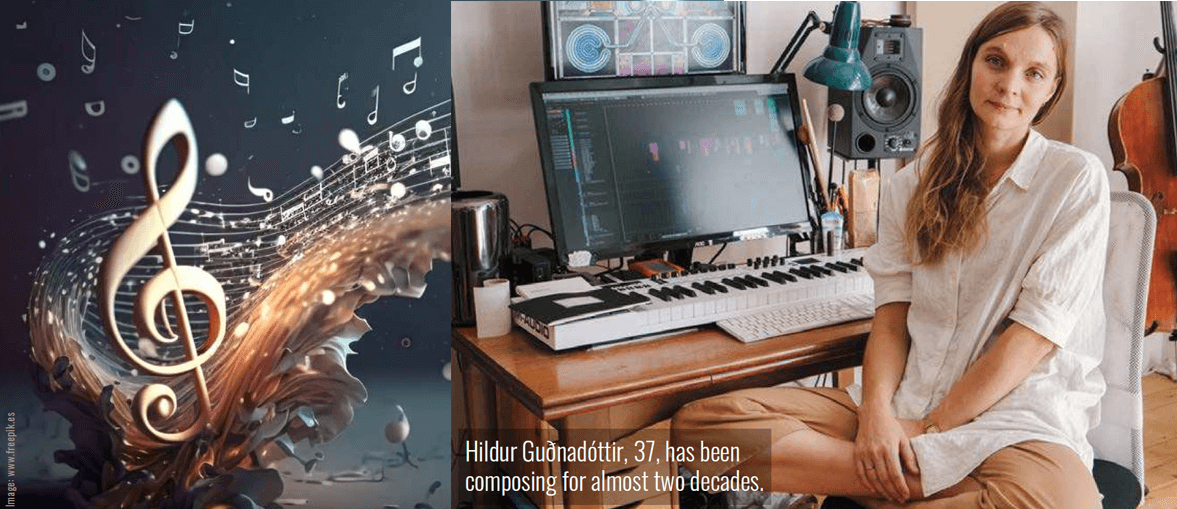

1. Introduction

Why are some sounds regarded

as ‘noise’ while others

are experienced as music? When

we perform or listen to music,

what occurs at the level of the

sound wave, the ear, and the

brain? How do musical abilities

emerge, develop, and refine as

one gains experience with music?

What gives the music such

a strong emotional impact and

the ability to influence social

behavior in so many different

cultural contexts? These are a

several of the frequent questions

that define the field of

“Music Psychology”.

In this essay, I’d want to

present a comprehensive overview

of classic and contemporary

studies in music psychology,

as well as critical critiques

of existing research. I want

to explore sound and music

on an acoustic level, describing

auditory phenomena in

terms of ear and brain function.

I’d want to focus on melody,

rhythm, and formal structure

perception and cognition, as

well as the origin and development

of musical talents, before

moving on to the most practical

components of music psychology:

gender in music, customers

behavior, the emotional power

of music. I sincerely believe that

my work may contribute to a

broader discussion of music’s

meaning in terms of its social,

emotional, philosophical, and

cultural relevance.

2. The subject of Music

Psychology

People have always chosen

specific sound patterns for

special attention all around the

world and for which we have

records. Some of these patterns

are what we refer to as ‘music.’

What distinguishes the sound

patterns that we identify as

music? What is it about these

sound patterns that has such a

profound meaning for humans?

All audible noises begin with

energy propagation into the

environment. It may be a gentle

breeze rustling a thousand fluttering

leaves, the plucking of harp strings, or the thud of a

bass drum. What makes some

air molecule dances ‘musical,’

whereas other air molecule

disturbances appear to produce

only sounds? Or is it the noise?

A symphonic orchestra concert

is a music. Music festivals

are music as well. Advertising

jingles are musical creations.

Many people consider church

bells, which ring out a basic

tune, to be music. Not every

sound, however, is music.

Could we come up with a

comparable list of noises that

everyone agrees aren’t music?

A sound pattern that is indicative

of non-music may be the

roar of a road drill or the sound

of a tractor. The bubbling of a

dishwasher or the screech of a

vacuum cleaner may strike us

as apparent examples of nonmusic.

What about the sound

of the waves crashing on the

shore? Is that a wolf howl? Or

perhaps a bird’s song?

While the extremes appear

to be well defined, there is no

obvious distinction between

music and noises that are not

music. Though we can fairly

clearly distinguish between

prototypical situations of music

and non-music, there are

many sound patterns that are

difficult to categorize as one or

the other.

Music definitions that are

all-encompassing may be difficult

to come by. Despite the hazy borders of the realm of

music, it appears that there are

auditory occurrences that we

can all agree constitute music,

and that have been agreed

upon in various cultures and

historical periods. Humans are

the ones who create and perceive

music. Performers must

master the abilities required to

produce organized sounds in

meaningful patterns. Listeners

must learn to perceive such

qualities of organized sound

patterns as music through

experience or education. A

comprehensive examination of

all of these talents, as different

as they are, is certainly needed.

The fusion of psychology and

music pave the way for such

investigations and opens up

options for research into a wide

range of themes. Newcomers

are sometimes taken aback by

the breadth and depth of this

vast discipline. The psychology

of music in the twenty-first

century is preoccupied with

several issues. It is concerned,

along with other things, with

how people perceive, respond

to, and produce music, also,

how they incorporate it into

their lives. These themes

include everything from how

the ear determines a tone’s

pitch to how music is used

to express or change moods.

Though cognitive psychology is

heavily used in this discipline,

it also draws on many other

schools of psychology, sensation

and perception, neuropsychology,

developmental

psychology, social psychology,

and practical subjects such as

classroom management are all

examples of psychology.

Not only psychologists and

musicians are drawn to music

psychology, but also scientists

and researchers from a variety

of fields. Perspectives from

acoustics, neurology, musicology,

education, philosophy,

and ethnomusicology are also

included in this collection. Musical

performance necessitates

the development of a complex

set of abilities and a developing

body of knowledge that allows

for sensitive musical interpretation.

A composition must

first be created before it can be

performed. This, too, necessitates

a complex set of abilities.

Then there’s improvisation as

a creative endeavor; Western

jazz and Indian classical movement

performances are famous

examples. Innovative music

education techniques presume

that all children are musical

and immerse young children in

creative and sensitive musical

interaction with the goal of

building the foundations for a

lifetime of musicality.

Moreover, because music is

divided into many diverse musical

cultures across the world,

an anthropological approach

that emphasizes the study of

different human civilizations

and their music is also helpful

in understanding the psychology

of music. Finding out what

is universal across all musical

cultures and what appears to

be distinctive to each one sheds

a lot of insight on psychological

issues. These investigations

aid in distinguishing between

cultural sources of musical

repertoire characteristics and

those that may arise from the

biological underpinnings of

musical perception.

3. Music and gender

The widespread categorization

of instruments and

performance genres as male or

female- appropriate has been

recorded by anthropologists

and historians. Koskoff (1995),

for example, demonstrates that

while gender stereotyping in

music took different forms in

different societies at different

eras, its consequences are

pervasive. Ideas concerning

gender-appropriate instrument

choice and manner of performance

have been particularly

prominent on occasions for

courting and ritual.

The Ga people of Ghana

have funeral rites that require

specific types of songs

to be sung solely by women.

Only women (and children) in

Afghanistan play a popular instrument

known as the ‘chang’

(a mouth harp). Steblin (1995,

p. 144), in a historical study

of musical stereotyping in

Western Europe, alludes to the

middle-class tradition of perceiving

the virginal and piano

as the most acceptable instruments

for ‘young girls’ because

they could be performed to

small groups of friends and

family within the home. Prior

to the mid-nineteenth century,

it was considered impolite for

women to perform in public,

and most orchestras refused to

recruit women (O’Neill, 1997).

By the time youngsters

take their first music lessons,

gender prejudices about music

have already emerged. Music

is typically stereotyped as a

more ‘feminine’ topic, with significantly more girls than

males taking music classes

and participating in musical

events during their school

years. Furthermore, children’s

instrument selections are

limited by what they consider

to be gender appropriate.

Many studies have consistently

shown that Western schoolage

children consider flutes,

violins, and clarinets to be appropriate

instruments for girls

to play, while drums, trumpets,

and guitars are considered to

be appropriate instruments for

boys (e.g., O’Neill & Boulton,

1996, who studied 9- to

11-year-old English children,

tho similar conclusions were

shown in young kids).

Some studies have found

that by providing instances of

gender and instrument mismatches

that conform to popular

expectations, children’s

opinions shift —however, the

impacts are minor and not

necessarily in the desired direction.

For example, Harrison

and O’Neill (2000) showed live

counter-gender-stereotyped

figures to youngsters and

found at least a modest shift

in indicated preferences for

gender-specific instrument

assignments among both girls

and boys. This strategy, on the

other hand, appears to lower

preference for instruments

considered to be gender- appropriate

in the past (For

example, after viewing a male

pianist, females expressed a

lower preference for the piano,

while boys expressed a lower

choice for the guitar after

watching a female guitarist).

Another Australian study that

employed video presentations

and counter- stereotypical

drawings discovered that girls

were more likely than boys to

experiment with non- traditional

player and instrument

combinations (Pickering and

Repacholi, 2001).

The number of female musicians

in professional bands

and orchestras is growing, and

the instruments they play are

diverse. However, this may be

more true of classical music

ensembles, whereas gender

equality in other genres, such

as jazz, has a long way to go.

McKeage (2004), for example,

revealed that in a study of over

600 students, substantially

fewer girls than men are active

in performing jazz in high

school or college. In addition,

despite the fact that 62% of

guys who played jazz in high

school continued to play in

college, just 26% of females

who played jazz in high school

did so. Female jazz musicians,

in particular, lacked confidence

in their ability to improvise.

Wehr-Flowers (2006)

discovered that girls in jazz

ensembles were significantly

less confident, nervous and

had a poorer feeling of selfefficacy

in jazz improvisation

than men, using a scale

that assesses attitudes toward

mathematics. Wehr-Flowers

says that while most studies

have not identified substantial

differences in male and female

jazz improvisation talents,

“we must therefore seek to

alternate causes for the gender

imbalance in the jazz sector”.

Females may not be socialized

to feel as comfortable as

males in participating in jazz

rituals such as showing off

one’s chops,’ and there is an

insufficient social framework

to support females because the

networks through which one

obtains informal jazz technique

training and advances one’s

career are predominantly male

(McKeage, 2004).

Music composition is one

area of music where women

are noticeably underrepresented.

According to research using

the ‘Goldberg paradigm,’ social

perception may have a part in

the tiny proportion of females

deemed to be prominent

composers in various genres of

music (Colley, North, & Hargreaves,

2003). This strategy was

first used in a famous 1968

research by Goldberg, which

found that journal publications

credited to John McKay

were rated more positively

than those ascribed to Joan

McKay in diverse domains of

competence.

Contemporary music compositions

were played to 64

undergrads who rated them

on a set of rating scales in

Colley’s study in 2005, which

extended the approach to the

musical realm.

Participants tended to

offer higher evaluations on

measures relating to musical

skill when the composers

were identified as Klaus Behne

and Simon Healy, compared

to Helena Behne and Sarah

Healy, even though the effects

were only marginally significant.

Higher ratings were

provided on various scales for

music claimed to female composers

under another scenario,

in which a brief biography was

added (that was the same for

all fake artists). ‘Where no information other than social

category is supplied, there

is more pro-male bias,’ the

scientists noted. If, on the

other hand, excellent biographies

are provided, readers

may conclude that the ladies

are especially committed and

have achieved a high degree of

success against the odds.

One hundred fifty-three

late-adolescent participants

were asked to evaluate six

works from the classical, jazz,

and new-age genres in a second

study by the same group

of researchers (North, Colley, &

Hargreaves, 2003). In this study,

(fictitious) composers’ names

and short biographical excerpts

regarding their history and

accomplishments were supplied

in all cases. The findings

diverged slightly from those

of the Colley et al. research,

with the jazz extracts providing

the most remarkable findings.

For starters, participants

definitely saw jazz composing

as a masculine occupation,

although reactions to classical

and new age music were

somewhat skewed the other

way. Second, female participants’

assessments for jazz

compositions exhibited strong

evidence of ‘pro-female prejudice,’

while male participants’

ratings revealed less striking

evidence of ‘anti- female bias.’

Furthermore, when ascribed to

a male composer, the identical

jazz tunes were evaluated as

‘softer’ and ‘warm,’ but when

assigned to a female composer,

they were perceived

as more ‘forceful,’ mirroring

preconceptions about male

and female composers. As with

many other characteristics of

musicality discussed in this

section, societal influences,

rather than sheer aptitude,

may account for discrepancies

in a degree of success and

prominence between male and

female composers.

4. Consumer behavior

in relation to music

as a social force

Kurt Lewin, a pioneering

social psychologist, stated

years ago that one’s social circumstances

have a significant

effect on directing conduct.

Though, as previously said,

this viewpoint has shifted in

recent years, there are compelling

claims that music has such

a function. These ideas may

be traced all the way back to

Plato, who claimed that different

musical modes might cause

different forms of conduct.

Empirical evidence suggests

that music may have a significant

influence on conduct and

that, unlike more explicit types

of persuasion such as verbal

messaging, it can happen

without people being aware

that music is driving their

behavior. This remark was

stated in research by North and

colleagues in the field of consumer

behavior (North, Hargreaves,

& McKendrick, 1997). Music

those evoked connections with

either France (e.g., a soulful

accordion piece) or Germany

(e.g., a soulful accordion piece)

played in the background while

shoppers meandered around

a grocery store (e.g., brassladen

Bierkeller music). The

researchers monitored customers

as they passed through

a wine aisle. Despite the fact

that most buyers were unaware

of the music, shoppers’ wine

tastes went toward the nation

represented by the music! As

a result, music’s influence on

behavior can be significant and

even subconscious.

A number of additional studies

have indicated that music has a

significant impact on people’s

mood and behavior in a variety

of commercial and industrial

environments. In a university

cafeteria, for example, North

and Hargreaves (1998) played

pop music, classical music, easy

listening music, or no sound.

Customers described the cafeteria

as ‘fun’ and ‘upbeat’ when

there was pop music playing,

‘sophisticated’ and ‘upmarket’

when there was classical music

playing, and ‘cheap’ and

‘down market’ when there was

easy listening music playing.

Customers were also willing to

spend more money for a list of

14 goods sold in the cafeteria

while popular music was playing

than when no music or easy

listening music was playing,

and they were willing to spend

the greatest money on the same

things when classical music

was playing. Another experiment

conducted at a university

cafeteria found that music can

influence consumers’ activity

rates. To be continued

Most of us have been there: out

with friends and their kids, you

catch yourself thinking “I wouldn’t

shout at her that way”. The rule in this

situation is to bite your tongue: unless

you see someone doing something

cruel to a child. ...

Last week, ministers again rejected

calls to prohibit physical punishment

for children in England. A year ago,

Nadhim Zahawi —then education minister—

said that the state shouldn’t be

“nannying people about how they bring

up their children”.

Zahawi is right that we should be

cautious about the state mandating

particular ways to parent. But banning

physical punishment is about giving

children equal protection in the law.

There is no legal defence to hitting another

adult, but in English law parents can rely on a defence of “reasonable

punishment” after striking a child.

There is no justification for this

beyond the idea that it’s a parent’s

right to use physical discipline if

they deem it necessary. There is now

incontrovertible evidence that smacking

children is harmful: a review of

69 longitudinal studies in the Lancet

found that physically punishing a child

is associated with worsening emotional

problems and behaviour. ... Physical

punishment is not associated with

any positive outcomes and within a

family it is a predictor of involvement

with child welfare services. This is

why Scotland and Wales have joined

more than 60 countries in banning it

altogether. ...

Read full text:

Most of us have been there: out

with friends and their kids, you

catch yourself thinking “I wouldn’t

shout at her that way”. The rule in this

situation is to bite your tongue: unless

you see someone doing something

cruel to a child. ...

Last week, ministers again rejected

calls to prohibit physical punishment

for children in England. A year ago,

Nadhim Zahawi —then education minister—

said that the state shouldn’t be

“nannying people about how they bring

up their children”.

Zahawi is right that we should be

cautious about the state mandating

particular ways to parent. But banning

physical punishment is about giving

children equal protection in the law.

There is no legal defence to hitting another

adult, but in English law parents can rely on a defence of “reasonable

punishment” after striking a child.

There is no justification for this

beyond the idea that it’s a parent’s

right to use physical discipline if

they deem it necessary. There is now

incontrovertible evidence that smacking

children is harmful: a review of

69 longitudinal studies in the Lancet

found that physically punishing a child

is associated with worsening emotional

problems and behaviour. ... Physical

punishment is not associated with

any positive outcomes and within a

family it is a predictor of involvement

with child welfare services. This is

why Scotland and Wales have joined

more than 60 countries in banning it

altogether. ...

Read full text:

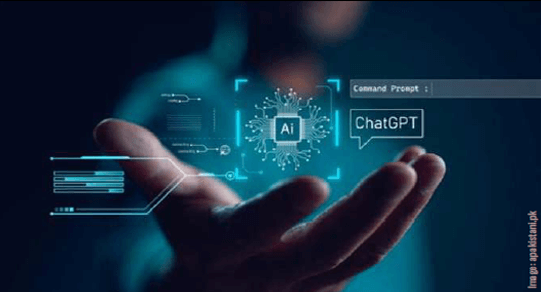

The AI landscape has started to move

very, very fast: consumer-facing

tools such as Midjourney and ChatGPT

are now able to produce incredible image

and text results in seconds based

on natural language prompts, and

we’re seeing them get deployed everywhere

from web search to children’s

books. However, these AI applications

are being turned to more nefarious

uses, including spreading malware. ...

Think about it: A lot of phishing attacks

and other security threats rely on

social engineering, duping users into

revealing passwords, financial information,

or other sensitive data. The

persuasive, authentic-sounding text

required for these scams can now be

pumped out quite easily, with no human

effort required, and endlessly tweaked

and refined for specific audiences.

In the case of ChatGPT, it’s important

to note that developer OpenAI has built

safeguards into it. ... However, these

protections aren’t too difficult to get

around: ChatGPT can certainly code, and

it can certainly compose emails. ... There

are already signs that cybercriminals are

working to get around the safety measures

that have been put in place.

We’re not particularly picking on

ChatGPT here, but pointing out what’s

possible once large language models

(LLMs) like it are used for more sinister

purposes. Indeed, it’s not too difficult

to imagine criminal organizations

developing their own LLMs and

similar tools. ... And it’s not just text

either: Audio and video are more difficult

to fake, but it’s happening as

well. ...

Read full text:

The AI landscape has started to move

very, very fast: consumer-facing

tools such as Midjourney and ChatGPT

are now able to produce incredible image

and text results in seconds based

on natural language prompts, and

we’re seeing them get deployed everywhere

from web search to children’s

books. However, these AI applications

are being turned to more nefarious

uses, including spreading malware. ...

Think about it: A lot of phishing attacks

and other security threats rely on

social engineering, duping users into

revealing passwords, financial information,

or other sensitive data. The

persuasive, authentic-sounding text

required for these scams can now be

pumped out quite easily, with no human

effort required, and endlessly tweaked

and refined for specific audiences.

In the case of ChatGPT, it’s important

to note that developer OpenAI has built

safeguards into it. ... However, these

protections aren’t too difficult to get

around: ChatGPT can certainly code, and

it can certainly compose emails. ... There

are already signs that cybercriminals are

working to get around the safety measures

that have been put in place.

We’re not particularly picking on

ChatGPT here, but pointing out what’s

possible once large language models

(LLMs) like it are used for more sinister

purposes. Indeed, it’s not too difficult

to imagine criminal organizations

developing their own LLMs and

similar tools. ... And it’s not just text

either: Audio and video are more difficult

to fake, but it’s happening as

well. ...

Read full text:

The relationship between the human

mind and body has been a subject

that has challenged great thinkers for

millennia, including the philosophers

Aristotle and Descartes. The answer,

however, appears to reside in the very

structure of the brain.

Researchers said [April 19th] they have

discovered that parts of the brain region

called the motor cortex that govern

body movement are connected with a

network involved in thinking, planning,

mental arousal, pain, and control of internal

organs, as well as functions such

as blood pressure and heart rate.

They identified a previously unknown

system within the motor cortex

manifested in multiple nodes that are

located in between areas of the brain

already known to be responsible for

movement of specific body parts —

hands, feet and face— and are engaged

when many different body movements

are performed together.

The researchers called this system

the somato-cognitive action network,

or SCAN, and documented its connections

to brain regions known to help

set goals and plan actions.

This network also was found to

correspond with brain regions that,

as shown in studies involving monkeys,

are connected to internal organs

including the stomach and adrenal

glands, allowing these organs to

change activity levels in anticipation of

...

The relationship between the human

mind and body has been a subject

that has challenged great thinkers for

millennia, including the philosophers

Aristotle and Descartes. The answer,

however, appears to reside in the very

structure of the brain.

Researchers said [April 19th] they have

discovered that parts of the brain region

called the motor cortex that govern

body movement are connected with a

network involved in thinking, planning,

mental arousal, pain, and control of internal

organs, as well as functions such

as blood pressure and heart rate.

They identified a previously unknown

system within the motor cortex

manifested in multiple nodes that are

located in between areas of the brain

already known to be responsible for

movement of specific body parts —

hands, feet and face— and are engaged

when many different body movements

are performed together.

The researchers called this system

the somato-cognitive action network,

or SCAN, and documented its connections

to brain regions known to help

set goals and plan actions.

This network also was found to

correspond with brain regions that,

as shown in studies involving monkeys,

are connected to internal organs

including the stomach and adrenal

glands, allowing these organs to

change activity levels in anticipation of

...

More than a billion adults around

the world live with elevated blood

pressure, a condition that puts individuals

at risk of damaging a variety of

organs, including the nervous system.

Though previous studies have linked

high blood pressure (hypertension)

with an increased risk of cognitive impairment,

the mechanisms behind the

decline in mental health has never been

known. Now an international team of

researchers has discovered which areas

of the brain are most likely to suffer

damage as the cardiovascular system is

put under strain.

“Our study has, for the first time,

identified specific places in the brain

that are potentially causally associated

with high blood pressure and cognitive

impairment,” says Jagiellonian University Medical College medical

biologist Mateusz Siedlinski. Siedlinski

and colleagues used a combination of

genetic and imaging data and observational

analyses from 33,000 individual

records in the UK Biobank to find the

damage caused by high blood pressure

that contributes to dementia. This

combined approach allowed the researchers

to identify where in the brain

long-term hypertension can cause the

structural changes that lead to declines

in cognitive function, and what those

changes look like in brain scan images.

“We thought these areas might be

where high blood pressure affects

cognitive function, such as memory

loss, thinking skills ...

Read full text

More than a billion adults around

the world live with elevated blood

pressure, a condition that puts individuals

at risk of damaging a variety of

organs, including the nervous system.

Though previous studies have linked

high blood pressure (hypertension)

with an increased risk of cognitive impairment,

the mechanisms behind the

decline in mental health has never been

known. Now an international team of

researchers has discovered which areas

of the brain are most likely to suffer

damage as the cardiovascular system is

put under strain.

“Our study has, for the first time,

identified specific places in the brain

that are potentially causally associated

with high blood pressure and cognitive

impairment,” says Jagiellonian University Medical College medical

biologist Mateusz Siedlinski. Siedlinski

and colleagues used a combination of

genetic and imaging data and observational

analyses from 33,000 individual

records in the UK Biobank to find the

damage caused by high blood pressure

that contributes to dementia. This

combined approach allowed the researchers

to identify where in the brain

long-term hypertension can cause the

structural changes that lead to declines

in cognitive function, and what those

changes look like in brain scan images.

“We thought these areas might be

where high blood pressure affects

cognitive function, such as memory

loss, thinking skills ...

Read full text

Boaz Rienshrieber advertised his

music classes with flyers stating

that “anyone can play.” Six years ago,

he was approached by a prospective

student who wanted to play guitar, but

her cerebral palsy severely inhibited her

ability to even hold the instrument.

He wanted to give her access to

something more expressive than the

shakers and peripheral percussion

instruments that students with cerebral

palsy are often relegated to. After doing

some searching, Rienshrieber put together

a development team to construct

an instrument perfectly tailored to her

physical abilities —and that’s how

the accessibility-focused instrument

Arcana Strum was born.

The Arcana Strum’s design is based

on the controls of a motorized wheelchair.

In its simplest form, the instrument

is intended to be placed on a table

or the musician’s lap, and is played by

a combination of large, color-coded

buttons and a lever used to strum. ...

Read full text:

Boaz Rienshrieber advertised his

music classes with flyers stating

that “anyone can play.” Six years ago,

he was approached by a prospective

student who wanted to play guitar, but

her cerebral palsy severely inhibited her

ability to even hold the instrument.

He wanted to give her access to

something more expressive than the

shakers and peripheral percussion

instruments that students with cerebral

palsy are often relegated to. After doing

some searching, Rienshrieber put together

a development team to construct

an instrument perfectly tailored to her

physical abilities —and that’s how

the accessibility-focused instrument

Arcana Strum was born.

The Arcana Strum’s design is based

on the controls of a motorized wheelchair.

In its simplest form, the instrument

is intended to be placed on a table

or the musician’s lap, and is played by

a combination of large, color-coded

buttons and a lever used to strum. ...

Read full text:

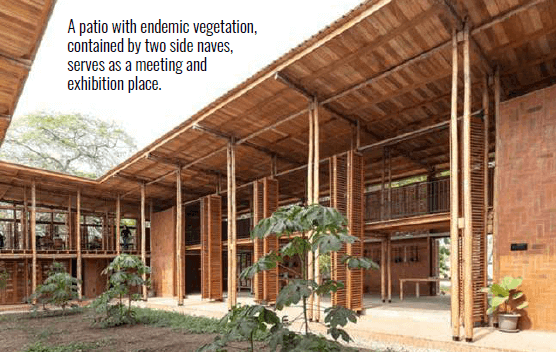

Natura Futura and architect Juan Carlos

Bamba design ‘Las Tejedoras’,

a Community Productive Development

Center, utilizing architecture as a tool

for the insertion, linkage, and support

of women weavers. The project seeks

to be a space for the intermediation of

productive development processes, linking

unemployed women through active

participation, the potentiation of local

artisan techniques, and the revitalization

of learning as an empowerment tool.

‘Las Tejedoras’ is located on the

outskirts of the urban community of

Chongón, Ecuador, with a population

of approximately 4,900 people, where

the majority are women who are not part of the economically active groups,

with little possibility of entering a labor

niche. Since 2009, the Young Living

Foundation, dedicated to generating

programs that promote the potential

of communities through education and

entrepreneurship, opened the Young

Living Academy where around 150 lowincome

children study, whose mothers

are part of the local productive workshops,

thus forming the Organization

of Bromelias Artisan Women, focused

on development through handmade

fabrics with natural fibers. ...

Read full text

Natura Futura and architect Juan Carlos

Bamba design ‘Las Tejedoras’,

a Community Productive Development

Center, utilizing architecture as a tool

for the insertion, linkage, and support

of women weavers. The project seeks

to be a space for the intermediation of

productive development processes, linking

unemployed women through active

participation, the potentiation of local

artisan techniques, and the revitalization

of learning as an empowerment tool.

‘Las Tejedoras’ is located on the

outskirts of the urban community of

Chongón, Ecuador, with a population

of approximately 4,900 people, where

the majority are women who are not part of the economically active groups,

with little possibility of entering a labor

niche. Since 2009, the Young Living

Foundation, dedicated to generating

programs that promote the potential

of communities through education and

entrepreneurship, opened the Young

Living Academy where around 150 lowincome

children study, whose mothers

are part of the local productive workshops,

thus forming the Organization

of Bromelias Artisan Women, focused

on development through handmade

fabrics with natural fibers. ...

Read full text

At the Henrico County Public Library,

where Barbara F. Weedman is the

director, she saw parents and caregivers

would struggle to use the computers

while balancing a baby on their lap or

keeping track of a busy toddler.

In 2017, when the library started

building a new location, Weedman had

an idea for work-play stations that

would give parents computer access

and a safe place to contain their baby

or child. She worked with the community

and a design group to bring the

idea to life, and when the Fairfield Area

Library opened in 2019, the Computer

Work and Play Stations were ready.

The Fairfield Area Library serves a

predominantly Black neighborhood

with many intergenerational homes.

These caregivers may not have internet

access at home, or they may just need

a quiet place away from home to get a

little work done,” Weedman says. ...

Read full text

At the Henrico County Public Library,

where Barbara F. Weedman is the

director, she saw parents and caregivers

would struggle to use the computers

while balancing a baby on their lap or

keeping track of a busy toddler.

In 2017, when the library started

building a new location, Weedman had

an idea for work-play stations that

would give parents computer access

and a safe place to contain their baby

or child. She worked with the community

and a design group to bring the

idea to life, and when the Fairfield Area

Library opened in 2019, the Computer

Work and Play Stations were ready.

The Fairfield Area Library serves a

predominantly Black neighborhood

with many intergenerational homes.

These caregivers may not have internet

access at home, or they may just need

a quiet place away from home to get a

little work done,” Weedman says. ...

Read full text

How microbes in the gut influence

the brain —and vice versa— is still

being unpicked. Studies have revealed

possible routes of communication that

include the immune system, branches of

the vagus nerve that run from the gut to

the brain, and interaction with the nerves

and synapses that control the function

of the gastrointestinal tract. If the links

could be understood, and harnessed, experts

say the impact could be profound.

Scientists hope that by shifting the composition

of microbes in the gut, either

by administering particular microbes or

helping beneficial microbes to thrive,

they may be able to help treat disorders

such as anxiety and depression —an approach

known as psychobiotics. ...

Early small studies, some industry

funded, found that consumption

of probiotics —good bacteria such as

bifidobacteria and lactobacilli— might

reduce psychological distress and even

affect brain activity in regions involved

in controlling the processing of emotion

and sensation.

One study found that taking a probiotic

was associated with a reduction in

negative mood. Another found that administering

Bifidobacterium longum to

patients with irritable bowel syndrome

reduced depression ...

Certainly the science suggests that

manipulating the gut microbiome

involves more than simply swallowing

a dose of good bacteria. “The diversity

of your diet leads the diversity of your

gut ...

Read full text:

How microbes in the gut influence

the brain —and vice versa— is still

being unpicked. Studies have revealed

possible routes of communication that

include the immune system, branches of

the vagus nerve that run from the gut to

the brain, and interaction with the nerves

and synapses that control the function

of the gastrointestinal tract. If the links

could be understood, and harnessed, experts

say the impact could be profound.

Scientists hope that by shifting the composition

of microbes in the gut, either

by administering particular microbes or

helping beneficial microbes to thrive,

they may be able to help treat disorders

such as anxiety and depression —an approach

known as psychobiotics. ...

Early small studies, some industry

funded, found that consumption

of probiotics —good bacteria such as

bifidobacteria and lactobacilli— might

reduce psychological distress and even

affect brain activity in regions involved

in controlling the processing of emotion

and sensation.

One study found that taking a probiotic

was associated with a reduction in

negative mood. Another found that administering

Bifidobacterium longum to

patients with irritable bowel syndrome

reduced depression ...

Certainly the science suggests that

manipulating the gut microbiome

involves more than simply swallowing

a dose of good bacteria. “The diversity

of your diet leads the diversity of your

gut ...

Read full text:

The human brain, we have learned,

adjusts and recalibrates temporal

perception. Our ability to encode

and decode sequential information,

to integrate and segregate simultaneous

signals, is fundamental to human

survival. It allows us to find our place

in, and navigate, our physical world. But

music also demonstrates that time perception

is inherently subjective —and

an integral part of our lives. “For the

time element in music is single,” wrote

Thomas Mann in his novel, The Magic

Mountain. “Into a section of mortal time

music pours itself, thereby inexpressibly

enhancing and ennobling what it fills.”

We conceive of time as a continuum,

but we perceive it in discretized units

—or as discretized units. It has long

been held that, just as objective time is dictated by clocks, subjective time (barring

external influences) aligns to physiological

metronomes. Music creates discrete

temporal units but ones that do not

typically align with the discrete temporal

units in which we measure time. Rather,

music embodies (or, rather, is embodied

within) a separate, quasi-independent

concept of time, able to distort or negate

“clock-time.” This other time creates

a parallel temporal world in which we

are prone to lose ourselves, or at least to

lose all semblance of objective time.

In recent years, numerous studies

have shown how music hijacks

our relationship with everyday time.

For instance, more drinks are sold in

bars when with slow-tempo music,

which seems ...

Read full text:

The human brain, we have learned,

adjusts and recalibrates temporal

perception. Our ability to encode

and decode sequential information,

to integrate and segregate simultaneous

signals, is fundamental to human

survival. It allows us to find our place

in, and navigate, our physical world. But

music also demonstrates that time perception

is inherently subjective —and

an integral part of our lives. “For the

time element in music is single,” wrote

Thomas Mann in his novel, The Magic

Mountain. “Into a section of mortal time

music pours itself, thereby inexpressibly

enhancing and ennobling what it fills.”

We conceive of time as a continuum,

but we perceive it in discretized units

—or as discretized units. It has long

been held that, just as objective time is dictated by clocks, subjective time (barring

external influences) aligns to physiological

metronomes. Music creates discrete

temporal units but ones that do not

typically align with the discrete temporal

units in which we measure time. Rather,

music embodies (or, rather, is embodied

within) a separate, quasi-independent

concept of time, able to distort or negate

“clock-time.” This other time creates

a parallel temporal world in which we

are prone to lose ourselves, or at least to

lose all semblance of objective time.

In recent years, numerous studies

have shown how music hijacks

our relationship with everyday time.

For instance, more drinks are sold in

bars when with slow-tempo music,

which seems ...

Read full text:

There is a misconception that the

ocean behaves like a bathtub. There

are two major reasons why sea levels are

rising. One is that the ocean is warming,

and it needs more space and expands.

The other one is that ice sheets and

glaciers are melting, and they put more

mass into the ocean. But if we look locally,

there are a lot of factors that lead

to regionally varying sea level rise.

We have changes in ocean circulation.

In the simplest form, winds over the

ocean push water masses from one side

to the other. That can lead to changes in

sea level over several years to decades.

The same is true for ocean currents.

If we put water into the ocean by ice

sheets or glaciers that are melting, their

gravitational field is also changed. Here,

there are three things that happen: You

put mass into the ocean, so sea levels

rise globally on average. But then, the

ice sheet is a heavy body of mass, and

due to its mass, it attracts the water of

the surrounding ocean, like the moon

generates tides. So as that ice sheet

melts you reduce that gravitational

attraction, and the water migrates

away from the ice sheet. And then at

the same time, the weight of the ice

sheet also becomes less, and it leads to

uplift of the ground below. So it leads

to sea level fall near the ice sheets but

sea level rise in what we call far-field

—like here in Louisiana, for instance.

Then, lastly, in particular here in

Louisiana, it’s not only the ocean that

is rising, but it’s also the land that

is sinking. ...

There is a misconception that the

ocean behaves like a bathtub. There

are two major reasons why sea levels are

rising. One is that the ocean is warming,

and it needs more space and expands.

The other one is that ice sheets and

glaciers are melting, and they put more

mass into the ocean. But if we look locally,

there are a lot of factors that lead

to regionally varying sea level rise.

We have changes in ocean circulation.

In the simplest form, winds over the

ocean push water masses from one side

to the other. That can lead to changes in

sea level over several years to decades.

The same is true for ocean currents.

If we put water into the ocean by ice

sheets or glaciers that are melting, their

gravitational field is also changed. Here,

there are three things that happen: You

put mass into the ocean, so sea levels

rise globally on average. But then, the

ice sheet is a heavy body of mass, and

due to its mass, it attracts the water of

the surrounding ocean, like the moon

generates tides. So as that ice sheet

melts you reduce that gravitational

attraction, and the water migrates

away from the ice sheet. And then at

the same time, the weight of the ice

sheet also becomes less, and it leads to

uplift of the ground below. So it leads

to sea level fall near the ice sheets but

sea level rise in what we call far-field

—like here in Louisiana, for instance.

Then, lastly, in particular here in

Louisiana, it’s not only the ocean that

is rising, but it’s also the land that

is sinking. ...

The COP15 agreement and its pledge

to preserve 30% of the world’s

biodiversity by 2030 (30×30) may have

sounded like a resounding success for

conservation around the world. However,

according to the Rainforest Foundation,

this could potentially impact up to

300 million people across the world.

Protecting our planet’s wildlife is a

crucial defense against the biodiversity

crisis. Depending on the context, restricting

access to vulnerable ecosystems

is crucial for preserving endangered

species. However, if our means

of doing so is by rehashing conservation

methods that ignore Indigenous

knowledge and needs, then COP15’s

30×30 push could produce far more

harm than good.

Today, we need to fuse international, modern ecological understanding with

local knowledge and the traditional

conservation methods that come with

it. That’s why it is crucial for local

representatives to be given both a

voice and representation at international

conservation conferences, and

at the private conservation funding

meetings where conservation land

demarcation is decided.

Research shows that while the

world’s 370 million Indigenous

peoples make up less than 5% of

the world’s total human population,

they manage over 25% of the world’s

land surface, and support 80% of the

world’s biodiversity. ...

Read full text:

The COP15 agreement and its pledge

to preserve 30% of the world’s

biodiversity by 2030 (30×30) may have

sounded like a resounding success for

conservation around the world. However,

according to the Rainforest Foundation,

this could potentially impact up to

300 million people across the world.

Protecting our planet’s wildlife is a

crucial defense against the biodiversity

crisis. Depending on the context, restricting

access to vulnerable ecosystems

is crucial for preserving endangered

species. However, if our means

of doing so is by rehashing conservation

methods that ignore Indigenous

knowledge and needs, then COP15’s

30×30 push could produce far more

harm than good.

Today, we need to fuse international, modern ecological understanding with

local knowledge and the traditional

conservation methods that come with

it. That’s why it is crucial for local

representatives to be given both a

voice and representation at international

conservation conferences, and

at the private conservation funding

meetings where conservation land

demarcation is decided.

Research shows that while the

world’s 370 million Indigenous

peoples make up less than 5% of

the world’s total human population,

they manage over 25% of the world’s

land surface, and support 80% of the

world’s biodiversity. ...

Read full text:

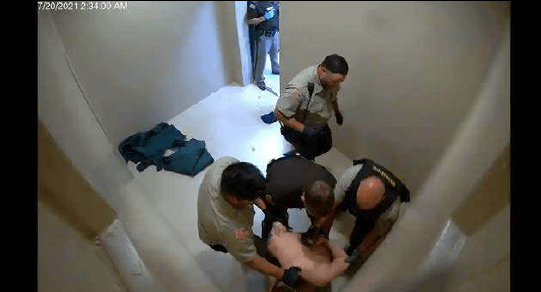

New surveillance video from inside

an Indiana jail shows how

a 29-year-old man who died in the

summer of 2021 from dehydration and

malnutrition was left naked in solitary

confinement for three weeks with no

medical attention.

The footage was released on Wednesday

[April 12th] by the family of Joshua

McLemore as part of a federal civil

rights lawsuit against Jackson county,

Indiana. The suit accuses the local sheriff,

jail commander and medical staff

of causing McLemore’s death through

deliberate indifference, neglect and

unconstitutional jail conditions while he

was in a state of psychosis.

Disturbing videos, some of which

were reviewed by the Guardian, show

McLemore as he was left in a small,

windowless cell for 20 days straight in Jackson county jail in July and August

of 2021. The cell had no bed or bathroom

and had fluorescent lights on at

all hours.

In the footage, McLemore, who was

diagnosed with schizophrenia, appears

detached from reality, speaking gibberish,

rolling in filth and his own waste

and becoming clearly emaciated. He

received daily meals through a small

slot in his jail door, but appears to have

rarely eaten them. He had extended

human interactions on only four occasions

—when guards used intense force

and restraint devices to drag him out to

clean the cell or give him a shower.

McLemore ultimately lost 45lbs during

his stay, but never saw a doctor or

mental health professional ...

New surveillance video from inside

an Indiana jail shows how

a 29-year-old man who died in the

summer of 2021 from dehydration and

malnutrition was left naked in solitary

confinement for three weeks with no

medical attention.

The footage was released on Wednesday

[April 12th] by the family of Joshua

McLemore as part of a federal civil

rights lawsuit against Jackson county,

Indiana. The suit accuses the local sheriff,

jail commander and medical staff

of causing McLemore’s death through

deliberate indifference, neglect and

unconstitutional jail conditions while he

was in a state of psychosis.

Disturbing videos, some of which

were reviewed by the Guardian, show

McLemore as he was left in a small,

windowless cell for 20 days straight in Jackson county jail in July and August

of 2021. The cell had no bed or bathroom

and had fluorescent lights on at

all hours.

In the footage, McLemore, who was

diagnosed with schizophrenia, appears

detached from reality, speaking gibberish,

rolling in filth and his own waste

and becoming clearly emaciated. He

received daily meals through a small

slot in his jail door, but appears to have

rarely eaten them. He had extended

human interactions on only four occasions

—when guards used intense force

and restraint devices to drag him out to

clean the cell or give him a shower.

McLemore ultimately lost 45lbs during

his stay, but never saw a doctor or

mental health professional ...

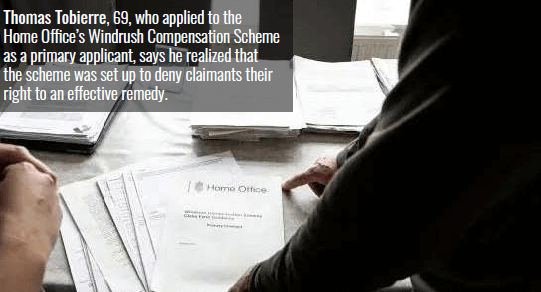

Let’s start from the beginning. After

1948, thousands of people from

Caribbean islands moved to the UK

—

named the “Windrush generation”

because many arrived on the ship HMT

Empire Windrush. They travelled to

the UK with the legal right to permanently

live and work there, but failure

one: the UK government never issued

them documentation so they could later

prove their lawful status in the UK.

In 2010, failure two: the UK government

destroyed the Windrush landing

cards that might have been used to

prove their lawful status. That year is

key to the story for another reason. It’s

when a new set of proposals emerged

—what the UK government eventually

called its “hostile environment policy.”

It established a set of requirements

designed to prevent access to services for anyone unable to prove their immigration

status. Its stated aim was to

make the requirements so difficult they

would push people to leave the country.

Thus, failure three: thousands of longterm,

lawful residents of the UK —mostly

Black Britons— suddenly found themselves

targets of an ill-conceived antiimmigrant

policy. ... The impacts were

devastating. People lost jobs, homes,

health care, pensions, and benefits. In

many cases, they were detained, deported,

and separated from their families.

Eventually, in 2018, the government

apologized for the scandal, and

in the following year, they opened the

Windrush Compensation Scheme. ...

Which brings us to today and failure

four: the compensation scheme itself

is failing ...

Let’s start from the beginning. After

1948, thousands of people from

Caribbean islands moved to the UK

—

named the “Windrush generation”

because many arrived on the ship HMT

Empire Windrush. They travelled to

the UK with the legal right to permanently

live and work there, but failure

one: the UK government never issued

them documentation so they could later

prove their lawful status in the UK.

In 2010, failure two: the UK government

destroyed the Windrush landing

cards that might have been used to

prove their lawful status. That year is

key to the story for another reason. It’s

when a new set of proposals emerged

—what the UK government eventually

called its “hostile environment policy.”

It established a set of requirements

designed to prevent access to services for anyone unable to prove their immigration

status. Its stated aim was to

make the requirements so difficult they

would push people to leave the country.

Thus, failure three: thousands of longterm,

lawful residents of the UK —mostly

Black Britons— suddenly found themselves

targets of an ill-conceived antiimmigrant

policy. ... The impacts were

devastating. People lost jobs, homes,

health care, pensions, and benefits. In

many cases, they were detained, deported,

and separated from their families.

Eventually, in 2018, the government

apologized for the scandal, and

in the following year, they opened the

Windrush Compensation Scheme. ...

Which brings us to today and failure

four: the compensation scheme itself

is failing ...

Organizations in Wisconsin are

asking for the public’s help after a

weather phenomenon is causing loons

to fall out of the sky. According to the

Raptor Education Group, Inc., there

have been multiple calls [April 21st]

about loons on land and small ponds.

The group says it appears there is a

loon fallout happening.

A loon fallout happens when atmospheric

conditions cause migrating

loons to develop ice on their body as

they fly at high altitudes. This then

causes the loons to crash land because

they are not able to fly due to the

weight of ice on their body. The ice also

can interfere with the loon’s flight ability.

Experts say that the current ice/rain

and unstable air currents are a perfect

set-up for this phenomenon to happen. Loons are not able to walk, which is

why groups are asking for residents to

help. Anyone who comes across a loon

on land is asked to call REGI, Loon

Rescue or their local wildlife center for

advice. Officials pleaded to not take

loons to small ponds for release, they

reportedly need a quarter mile or more

of open water to run across and get

airborne. Loons also have sharp beaks

and use said beaks for defense. Officials

said you can cover them with a blanket

to contain them. When it comes to

transporting, officials say you can use a

Rubbermaid container with air holes in

the top. Towels should be placed at the

bottom of the container or box to help

prevent injury. ...

Organizations in Wisconsin are

asking for the public’s help after a

weather phenomenon is causing loons

to fall out of the sky. According to the

Raptor Education Group, Inc., there

have been multiple calls [April 21st]

about loons on land and small ponds.

The group says it appears there is a

loon fallout happening.

A loon fallout happens when atmospheric

conditions cause migrating

loons to develop ice on their body as

they fly at high altitudes. This then

causes the loons to crash land because

they are not able to fly due to the

weight of ice on their body. The ice also

can interfere with the loon’s flight ability.

Experts say that the current ice/rain

and unstable air currents are a perfect

set-up for this phenomenon to happen. Loons are not able to walk, which is

why groups are asking for residents to

help. Anyone who comes across a loon

on land is asked to call REGI, Loon

Rescue or their local wildlife center for

advice. Officials pleaded to not take

loons to small ponds for release, they

reportedly need a quarter mile or more

of open water to run across and get

airborne. Loons also have sharp beaks

and use said beaks for defense. Officials

said you can cover them with a blanket

to contain them. When it comes to

transporting, officials say you can use a

Rubbermaid container with air holes in

the top. Towels should be placed at the

bottom of the container or box to help

prevent injury. ...

For the first time in the world,

researchers at Tel Aviv University

recorded and analyzed sounds distinctly

emitted by plants. The clicklike

sounds, similar to the popping

of popcorn, are emitted at a volume

similar to human speech, but at high

frequencies, beyond the hearing range

of the human ear.

The researchers: “We found that

plants usually emit sounds when they

are under stress, and that each plant

and each type of stress is associated

with a specific identifiable sound.

While imperceptible to the human ear,

the sounds emitted by plants can probably

be heard by various animals, such

as bats, mice, and insects.”

The study was led by Prof. Lilach Hadany,

together with Prof. Yossi Yovel, and research students Itzhak Khait and

Ohad Lewin-Epstein, in collaboration

with other researchers at Tel Aviv University.

The paper was published in the

scientific journal Cell.

At the first stage of the study the

researchers placed plants in an acoustic

box in a quiet, isolated basement

with no background noise. Ultrasonic

microphones recording sounds

at frequencies of 20-250 kilohertz

(the maximum frequency detected by

a human adult is about 16 kilohertz)

were set up at a distance of about 10cm

from each plant. The study focused

mainly on tomato and tobacco plants,

but wheat, corn, cactus and henbit

were also recorded. ...

For the first time in the world,

researchers at Tel Aviv University

recorded and analyzed sounds distinctly

emitted by plants. The clicklike

sounds, similar to the popping

of popcorn, are emitted at a volume

similar to human speech, but at high

frequencies, beyond the hearing range

of the human ear.

The researchers: “We found that

plants usually emit sounds when they

are under stress, and that each plant

and each type of stress is associated

with a specific identifiable sound.

While imperceptible to the human ear,

the sounds emitted by plants can probably

be heard by various animals, such

as bats, mice, and insects.”

The study was led by Prof. Lilach Hadany,

together with Prof. Yossi Yovel, and research students Itzhak Khait and

Ohad Lewin-Epstein, in collaboration

with other researchers at Tel Aviv University.

The paper was published in the

scientific journal Cell.

At the first stage of the study the

researchers placed plants in an acoustic

box in a quiet, isolated basement

with no background noise. Ultrasonic

microphones recording sounds

at frequencies of 20-250 kilohertz

(the maximum frequency detected by

a human adult is about 16 kilohertz)

were set up at a distance of about 10cm

from each plant. The study focused

mainly on tomato and tobacco plants,

but wheat, corn, cactus and henbit

were also recorded. ...

Adidas Solar Headphones

are constantly recharging themselves

with any and all available light,

whether natural or artificial. From the

app (available for iOS and Android),

you can view detailed charging data.

www.adidasheadphones.com

Adidas Solar Headphones

are constantly recharging themselves

with any and all available light,

whether natural or artificial. From the

app (available for iOS and Android),

you can view detailed charging data.

www.adidasheadphones.com

Medical conditions can

affect children’s grip or

hand function, from

Cerebral Palsy to Guillain-

Barré syndrome,

Muscular Dystrophy